Debut albums come in all flavors. Some barely hint at the artistry to come; others are solid first salvos only to be eclipsed by stronger and/or further refined efforts. Below, I’ve chosen perhaps that rarest breed: the fully-formed release that kicked off careers both fleeting and venerable and were also arguably never topped by anything else the artist would make. To be eligible, they must have recorded at least more than one follow-up. Here are ten favorites in chronological order:

Leonard Cohen, Songs of Leonard Cohen (1968)

Probably this list’s most contentious choice given I’m Your Man (1988), the first Cohen I ever heard (and loved) is its equal and fully holds up despite radically different and deliberately dinky period production. Alas, this debut plays more like a greatest hits compilation than the one he’d release seven years later: credit the three songs later brilliantly used in McCabe & Ms. Miller, but there’s also “Suzanne”, “Master Song”, “So Long Marianne”, “Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye”—even Lenny’s off-key bleating at the end of “One of Us Cannot Be Wrong” still charms me.

Violent Femmes, Violent Femmes (1983)

Maybe the most obvious choice here but this is a textbook example of a debut so definitive, so iconic that Gordon Gano and co. arguably haven’t tried to top it. I don’t know how many officially released singles there were from this, but at least five of its ten tracks are undeniable standards (“Blister In the Sun”, “Kiss Off”, “Add It Up”, “Prove My Love”, “Gone Daddy Gone”) and most nonfans would likely struggle to name more than two or three songs from the rest of their catalog.

Deee-Lite, World Clique (1990)

“Groove Is In The Heart” remains one of a handful of songs I wholly fell in love with on first listen and it’s aged beautifully compared to most hits of its era. To a lesser extent, one could say the same of its parent album. Whether skewed towards Italo-house (“Good Beat”, “Power of Love”) retro-funk (“Who Was That?”, “Try Me On, I’m Very You”) or electro-pop (“What Is Love”, “E.S.P.”), World Clique is exuberant party music with substance that also doesn’t take itself too seriously (unlike their next two albums.)

Liz Phair, Exile In Guyville (1993)

An eighteen-track manifesto seemingly untouched by the outside world, it’s a pure distillation of Phair’s raw talent. Few first albums have expressed such palpable perspective, much less a feminine one so unapologetically, frankly sexual and forthcoming. It either came out at exactly the right time or it ended up shaping the times even if it didn’t trouble the monoculture much. When Phair did exactly that on Whip-Smart (1994) and the much-maligned Liz Phair (2003), the effect wasn’t as novel or powerful.

Soul Coughing, Ruby Vroom (1994)

A truly strange band that could’ve only ended up on a major label at the height of alt-rock, Soul Coughing’s mélange of beat poetry-derived vocals, jazz rhythm section and sample-heavy soundscapes was both instantly recognizable and really like nothing else. So inspired was their debut that it gave off the impression they could be the 90s answer to Talking Heads. Instead, they ran out of gas after three increasingly conventional albums, suggesting such a notion was too good to be true even if for a brief shining moment it might have been.

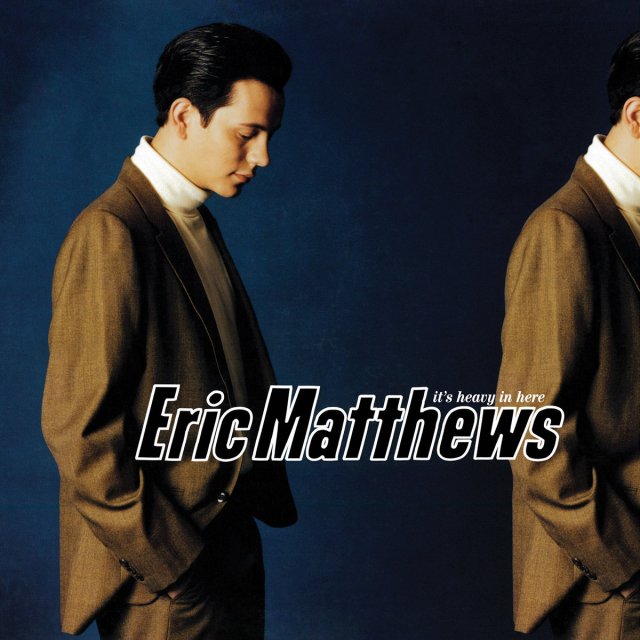

Eric Matthews, It’s Heavy In Here (1995)

Whereas most 90s singer-songwriters took inspiration from John Lennon or Neil Young, breathy-voiced Matthews learned his stuff from Burt Bacharach and The Zombies’ Colin Blunstone, crafting intricate, opaque chamber-pop miniatures with guitars as prominent as the trumpet solos, cathedral organ, string quartets, etc. Call it an anachronism, but perhaps Matthews was (however unwittingly) playing the long game as, nearly thirty years on, this debut sounds as out-of-time as it ever did and also as fresh, brimming with little details and nuances ripe for discovery.

Morcheeba, Who Can You Trust? (1996)

The breaking point where “trip-hop” was not yet a genre to emulate but more of a happy accident, a sound stumbled upon when a DJ, a blues guitarist and a one-of-a-kind vocalist with a sweet but alluringly hazy tone all came together and their seemingly disparate contributions somehow gelled like smoothed-out alchemy. From the catchy, loping “Trigger Hippie” to the somber, hypnotic title track, it’s overall more of a sustained groove than a collection of discernible songs—a potency that they only intermittently recaptured when they later mostly eschewed grooves for songs.

The Avalanches, Since I Left You (2000)

Speaking of DJs and sampling, it took nearly sixteen years for this Australian collective to record a second album and a relatively scant four more years to release a third; whenever I listen to the first one, I can fathom why—a triumph of plunderphonics and fin de siècle attitude of “here’s where we’ve been, and here’s what’s next”, Since I Left You remains a singular point continually reverberating and a miracle of reappropriation so far-reaching it feels impossible to improve on—I don’t listen to it as much, but it’s still my favorite album of the 00’s.

Nellie McKay, Get Away From Me (2004)

This “delightful nutcase” (as a friend once correctly described her) released a debut so audacious, precocious, declarative and altogether stunning that I suspected it would be her Bottle Rocket or Reservoir Dogs (a great first effort in a career full of ‘em); unfortunately it ended up more of a Donnie Darko—one great glimpse of promise, followed by weird left turns and outright disappointments to the point where she’s settled for interpreting other people’s work, which she’s often gifted at doing. But I remember how much potential she once had.

Florence + The Machine, Lungs (2009)

Talk about the voice of a generation—Florence Welch, then in her early twenties made that very rare accomplishment of coming off as a *star* from the get-go with excellent tunes (“Dog Days Are Over”, “Rabbit Heart (Raise It Up)”) and an arresting, bold sound entirely worthy of and complimentary to that voice. Welch remains the most promising heir apparent to succeeding Kate Bush at the High Alter of Eccentric Female Divas, even if none of her subsequent work startles or transcends like Lungs (although 2015’s How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful comes close.)