A pretty good year for cinema! As always, a film is eligible if it’s first available in my area for theatrical or streaming release during the calendar year.

1. UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE

“What if Canada and in particular, that unloved inland metropolis of Winnipeg was colonized by Iran?” is the jumping-off point for writer/director/actor Matthew Rankin’s second feature, a considerable advance over his first, Twentieth Century while barely resembling it. A deadpan mashup of quirks learned from both Abbas Kiarostami and Guy Maddin, it’s the funniest movie I’ve seen in ages (or at least since Hundreds of Beavers). Also, one of the most original and unexpectedly moving, creating an outrageous mirror world from scratch and unspooling a narrative that concludes with the wisdom and epiphany of, well, a Kiarostami film.

2. RESURRECTION

To craft an ode to cinema itself traversing the entire 20th Century through five different genre-specific segments is a level of ambition all too rare in the streaming age. I knew director Bi Gan was one to watch after 2018’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night and this exceeded even those expectations. Like seeing both The Wizard of Oz and 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time (if each film were superimposed over the other, perhaps), Resurrection is Gan shooting for the stars and brilliantly firing on all cylinders.

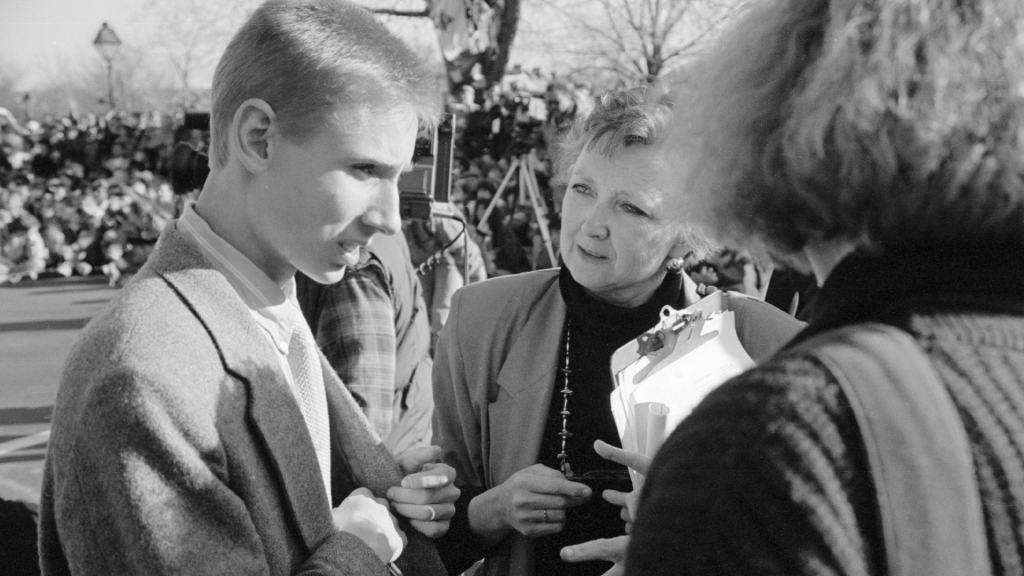

3. DEAF PRESIDENT NOW!

I wasn’t familiar with the 1988 eight-day, student-led protest at Gallaudet University, a Washington DC liberal arts college for the deaf against the appointment of a non-deaf president in lieu of two other deaf candidates. This documentary similarly feels like a bridge constructed to represent the deaf community and educate everyone else. Threading an excess of archival footage with modern day interviews, it emerges a portrait of a mobilized community pushing for change, genuinely inspiring without coming off as cloying. It’s hard not to get caught up in the sheer goodwill it exudes.

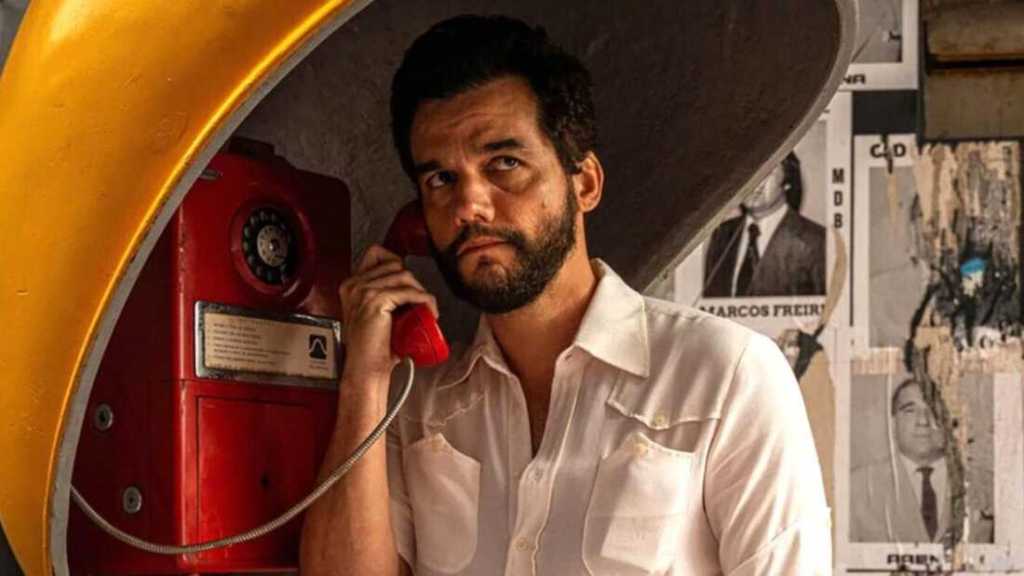

4. THE SECRET AGENT

Long worthy of such recent widespread attention, Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho’s latest draws from some the best parts of Aquarius and Bacurau (along with his great companion doc Pictures of Ghosts) and alchemizes them into a period thriller in love with movies and life itself. Additionally, Wagner Moura’s lead performance nearly transports the film in how he communicates and embodies the ambiguities and slipperiness of Filho’s zig-zagging narrative. Although set in a specific time and place, strong parallels to the here and now make this an essential example of art reflecting life.

5. IT WAS JUST AN ACCIDENT

Jafar Panahi has an enviable filmography (The White Balloon, Offside, No Bears, etc.) but it feels like everything he’s previously done has been building to this, his funniest and also most cathartic effort. Involving a ragtag group of people who believe they’ve stumbled upon their interrogator/torturer when they were imprisoned, It Was Just An Accident is something of a serious farce, carefully balancing its intentions while allowing for a heady, messy convergence of emotions and actions, considering both revenge and forgiveness and whether there’s justification for both.

6. ONE BATTLE AFTER ANOTHER

Nearly an ideal of contemporary, auteur-driven studio-made cinema. Of course, one could say the same for many of Paul Thomas Anderson’s films (but not all.) So, what makes this preferable to Licorice Pizza (or his previous Pynchon adaptation Inherent Vice) is tricky to parse; in this case, it comes down to how in tune it is with the current moment (it helps this is his first present-set piece since Punch-Drunk Love), though a sparking ensemble (Leo, Teyana and Benicio at their best with newcomer Chase Infiniti effortlessly commanding the screen) should not be underestimated.

7. CAUGHT BY THE TIDES

Jia Zhangke will never run out of ways to explore rapid change in 21st Century China or roles for his muse Zhao Tao to excel in, thank god. This one literally goes back to some of them, nimbly incorporating scenes and outtakes from his past filmography along with newly-shot footage to track how much China and, in particular, the Northern city of Datong has reconstructed itself between then and now. Also, an immersive, collage-like soundtrack spanning copious genres and traditions vividly amplifies a sense of a world forever in flux.

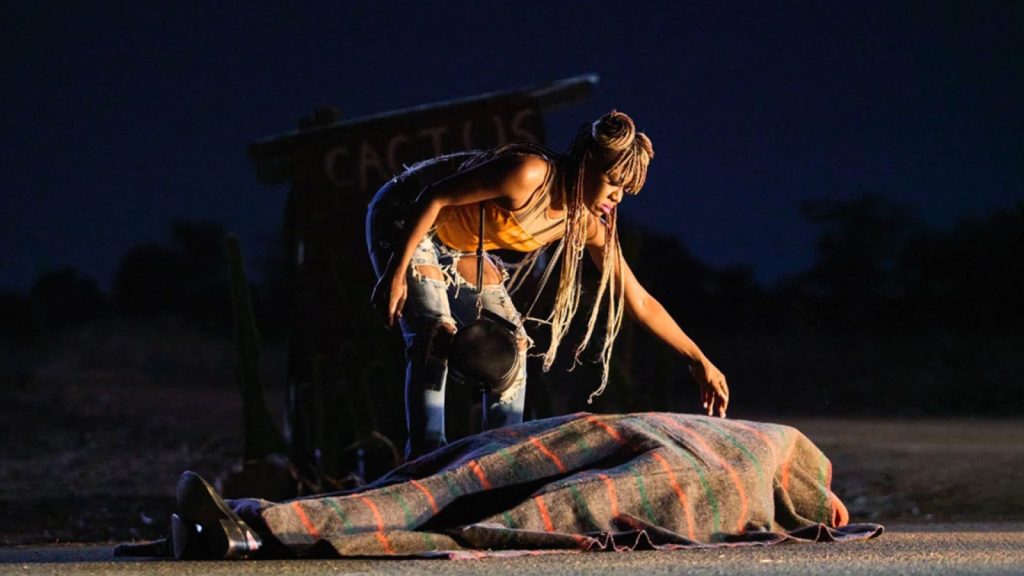

8. ON BECOMING A GUINEA FOWL

On my first festival viewing of this 15 months ago, I thought it drifted somewhat while finding authenticity in its portrait of an ultra-specific community; after a second watch last summer, I fully gleaned its durability and playful but profound dissection of family and how a secret can fester and explode but ultimately not change a mindset that refuses to accept or even see the truth. As with Bi Gan a few years ago, I can’t wait to see what Zambian director Rungano Nyoni (or her captivating lead Susan Chardy) does next.

9. REBUILDING

Between this and A Love Song, Max Walker-Silverman has become one of best American indie directors for how he focuses on such low-stakes but high-yielding stories about the human condition. Inspired by the Spring Creek Fire in southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley, Rebuilding is a mostly unsentimental study of loss and the struggle to recenter and focus on what matters and how to move forward. Maybe the best Josh O’Connor performance (out of 100?) this year but newcomer Lily LaTorre and veteran Amy Madigan both match him. (Speaking of which…)

10. WEAPONS

An Oscar for an unrecognizable Amy Madigan’s inspired, demented work would nearly make me as happy as the Emmy for Jeff Hiller last year but the beauty of Zach Cregger’s film extends far beyond his ringer cast member. I’m not all that into horror, but this was my favorite of that genre since Late Night With The Devil and possibly Get Out. With its powerful use of George Harrison’s “Beware of Darkness”, a high-concept narrative skillfully developed and deployed and its invigorating conclusion, it shows there’s hope for studio-made entertainment yet.

11. THE MASTERMIND

A less warm-and-fuzzy companion to the similarly-set The Holdovers; fortunately, Josh O’Connor and Kelly Reichardt are an ideal star/director pair for such a proposition; the period design and percussive-heavy jazz score also complement rather than detract from the film’s socio-economical critique.

12. NO OTHER LAND

Finally widely available to view, this Academy Award-winning doc about a displaced Palestinian village embodies what Roger Ebert said about film serving as an “empathy machine”, its urgency heightened by humanity struggling to persevere in the face of brutality.

13. NEXT SOHEE

The first half of this South Korean drama is almost excruciating to watch but it’s necessary in order for the second half to be effective; Bae Doona’s masterful, almost minimalist performance in the latter is also essential. As our surrogate, we discover the same infuriating hard truths as she does—an understanding of a broken system with no easy fixes.

14. IF I HAD LEGS, I’D KICK YOU

Filmmaker Mary Bronstein knows how to ramp up tension to the breaking point but crucially she also allows for some release without letting her lead off the hook. As much as I generally love Jessie Buckley (she’s no slouch in the uneven Hamnet), this is Rose Byrne’s moment.

15. TRAIN DREAMS

I haven’t read the book but as a film, this was gorgeously shot and edited with agility to the point where I was rarely bored or distracted. Perhaps as close to capturing the essence of a lifetime a single feature can likely reach. Joel Edgerton disappears into another role but enables us to see, feel and fully comprehend the part he plays.

16. TWINLESS

James Sweeney’s latest vindicates the promise of Straight Up, taking a fairly outlandish premise and making a meal out of it. Dylan O’Brien and Aisling Franciosi are both great (esp. the former in a dual role) but it’s Sweeney’s unique voice that powers this messy, yearning, accomplished character study.

17. PLAINCLOTHES

An impressive debut from director Carmen Emmi. Really develops a palpable sense of time and place to give viewers a context for what the characters struggle with and how they seek release; it also has great work from Tom Blyth, Russell Tovey and Maria Dizzia.

18. OCEANS ARE THE REAL CONTINENTS

Gives one such a complete sense of what it’s like to actually be in the backwater of San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba (black-and-white cinematography, slow-cinema rhythms and all) with its minuscule, ultra-specific focus. Plus, you get an extraordinary puppet show near the end.

19. APRIL

An absorbing if curious blend of Tarkovsky-style mysticism and Mungiu-like kitchen-sink realism. The static camera, creepily effective sound design and stark, darkly gorgeous landscapes all evoke a feeling of discomfort and the feminist POV hits its targets without coming off as obvious or sanctimonious.

20. DEAD MAIL

Smart enough to transcend its low-budget limitations, this curiosity blends a Sam Raimi-derived 80s aesthetic with stalker-horror tropes and rabbit-hole like narrative developments to arrive at an unexpected tonal place, a singularity of the sort reminding me why I occasionally seek out movies I know nothing about.

21. MISERICORDIA

22. MY MOM JAYNE

23. WE STRANGERS

24. THE PLAGUE

25. GRAND TOUR

26. FAMILIAR TOUCH

27. PAVEMENTS

28. HEDDA

29. SECRET MALL APARTMENT

30. EEPHUS

31. THE TESTAMENT OF ANN LEE

32. EVERY LITTLE THING

33. VIET AND NAM

34. THANK YOU VERY MUCH

35. BLUE SUN PALACE

36. COME SEE ME IN THE GOOD LIGHT

37. GRIFFIN IN SUMMER

38. LEFT-HANDED GIRL

39. THE BALLAD OF WALLIS ISLAND

40. THE PERFECT NEIGHBOR

ALSO RECOMMENDED:

A Nice Indian Boy, A Traveler’s Needs, Bob Trevino Likes It, Julie Keeps Quiet, No Other Choice, Nouvelle Vague, On Swift Horses, Peter Hujar’s Day, Sharp Corner, Sinners, Souleymane’s Story, The Assessment, The History of Sound, The Piano Accident, The Wedding Banquet, Who By Fire

ON MY WATCHLIST:

Blue Moon, Cloud, East of Wall, Eternity, Father Mother Sister Brother, Porcelain War, Splitsville, Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted, The Baltimorons, The Queen of My Dreams, The Voice of Hind Rajab, Wake Up Dead Man