(My 100 favorite albums in chronological order: #32 – released April 1992)

Track listing: The Ballad of Peter Pumpkinhead / My Bird Performs / Dear Madam Barnum / Humble Daisy / The Smartest Monkeys / The Disappointed / Holly Up On Poppy / Crocodile / Rook / Omnibus / That Wave / Then She Appeared / War Dance / Wrapped In Grey / The Ugly Underneath / Bungalow / Books Are Burning

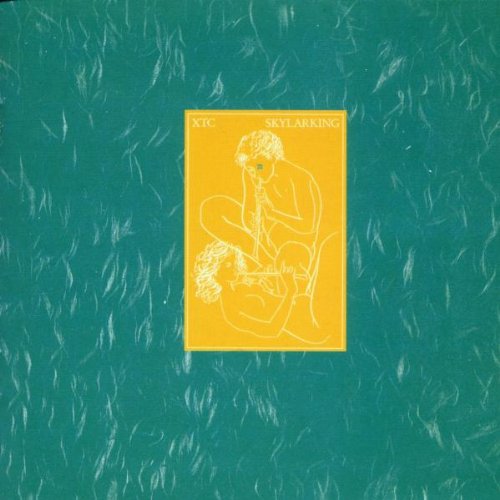

Three years after Skylarking resuscitated XTC’s career in America, this venerable British trio released Oranges and Lemons, a double album packed with big, bold psychedelic pop. Amiable lead single “The Mayor of Simpleton” topped Billboard’s Modern Rock chart (and also became the band’s sole song to make the magazine’s Hot 100 singles chart); it was also the first XTC album I ever heard. For that reason, I still retain a soft spot for it, despite its numerous flaws (the production’s a little dated and it could’ve greatly benefited from being ten or twelve tracks long instead of fifteen). Still, I nearly wrote about it here instead of the band’s next album, Nonsuch, debating between the two for some time.

On first listen, Nonsuch seemingly has the same exact flaws as its more-celebrated predecessor: it’s even two tracks longer and the production also occasionally betrays its age (particularly when synthesizers stand in for real woodwinds, like the faux-clarinet providing the main hook in “War Dance”, which bandleader Andy Partridge likened to a “singing penis”.) Not wanting to employ Skylarking’s Todd Rundgren or Paul Fox (the novice/XTC superfan who helmed Oranges and Lemons) again, the band ended up with Gus Dudgeon, best known for producing Elton John’s classic album run in the early-mid ‘70s. As vividly detailed in the book Song Stories, the flamboyant, older Dudgeon instantly clashed with the band and Partridge in particular, whom Dudgeon barred from attending the original mix sessions (which turned out disastrously, ending up with Gus getting the sack and a replacement engineer hired to finish the album).

Despite all this behind-the-scenes drama, Nonsuch turned out a coherent, consistent record. Somehow, all of these disparate-sounding songs seem to fit together to the degree that the band can get away with barely including a pause between some of the tracks; the transitions, too, are often stunning, the sweetness of “Then She Appeared” magically emerging from the cacophony that closes out “That Wave”, or the ambiguous ending of “Rook” nearly resolved by the abrupt but welcoming upbeat, declarative intro of “Omnibus”. On the whole, it has arguably aged better than any other late-period XTC release except for Skylarking. As usual, the band were slightly out of step with the times—released at the height of grunge, Nonsuch may have found a wider audience had it come out two years before (building on the momentum of Oranges and Lemons) or perhaps two years later (just in time for Britpop, which would not have existed without the band’s massive influence).

Nonsuch’s first three tracks comprise one of the strongest opening sequences in the band’s oeuvre: a grand, epic-length story song brimming with allegory and blaring harmonica, “The Ballad of Peter Pumpkinhead” became XTC’s second (and final) number one US Modern Rock hit; if the band had never quit touring, one can imagine it as the likeliest song fans would sing along with in concert (next to “Senses Working Overtime”) given its simple yet immediate melody. “My Bird Performs”, the buoyant Colin Moulding song that follows is one of his best, all ringing guitars and romantic (but relatable) proclamations, sweetened by Guy Barker’s trumpet and Partridge’s effortless swoon of a backing vocal. And “Dear Madam Barnum” exhibits Partridge’s prowess in wrapping both the political (alternate title: “Dear Margaret Thatcher”) and the personal (nearly anticipating his forthcoming divorce from wife Marianne) in a catchy, confident jangle-pop package.

The rest of Nonsuch has no shortage of potential singles. An actual one, “The Disappointed”, was the band’s first UK top 40 hit in ten years, an anthem for broken hearts that’s both full of longing and defiantly upbeat, thanks to the charge of the guitars and the propelling beat under all that stirring orchestration. “Crocodile” covers the same ground lyrically but is far more playful, its loping, nagging rhythm an ideal foundation for the band to rock out with wicked exuberance. “Then She Appeared” is almost retro-goofy enough for the Dukes of Stratosphear, and while Partridge didn’t rate it too highly, Dudgeon was correct to think this gleaming slice of sunshine pop should have been a single. “Books Are Burning” shows that even this late in the game, XTC always ended their albums with a stunner, in this case a stately, bluesy hymn to the sanctity of the written word, played off by dueling guitar solos and a nice, if brief “Hey Jude”-like coda.

As with most XTC LPs, scattered in between all the perfect three (and four, and five) minute pop songs are peculiar, challenging and often just plain weird experiments that distinguish Nonsuch from anything else of its time. The latest in a string of Brian Wilson pastiches stretching back to Skylarking’s “Season Cycle”, “Humble Daisy” conjures a floating dreamland out of Mellotron, impish, electric harpsichord and a melody that repeatedly emerges and vanishes like the tides. A few shades darker, “That Wave” almost threatens to totally freak out, albeit in slow motion with Partridge’s elastic vocal rising and descending like a blustery wind, the song ending in a reverberating wash of noise. “The Ugly Underneath” goes to further extremes: a sinus-clearing stomp where Partridge sounds as youthful and incensed as he did thirteen years before on Drums and Wires (dig the way he lends the word “underneath” two extra syllables), it’s the loudest track here—that is, until the coda, an extended moment of grace where a regal, beatific organ calmly reprises the chorus’ melody.

Even Moulding stretches a bit on two of his four compositions. From its first isolated, echoing guitar chords, you can detect the stillness, the wonderment and yes, the pretentiousness in “The Smartest Monkeys” and you would not be laughed out of the room if you mistook it for a Yes or Genesis album cut. And yet, it’s as melodically sound and everyman-focused as any of Moulding’s songs that you can almost forgive him for including that exceptionally wonky synth solo. Just as arty but far more dissonant, “Bungalow” evokes the remote, foggy, grey British seaside with as much detail as Morrissey’s “Everyday Is Like Sunday”. However, Moulding is more an observer than a critic—although this curious little reverie doesn’t lack melancholia, it ultimately feels wistful, lovingly detailing a crumbling paradise that has lost more than a bit of luster but retains its special, almost enviable otherness.

Still, it’s Partridge who provides Nonsuch with two songs that are among the furthest reaching and most affecting in his career. Both convey a newfound maturity suggesting a willingness to age gracefully rather than try to foolishly recapture past triumphs. “Rook” opens with a contemplative sequence of isolated, elongated piano chords, each one occurring before the previous one entirely disappears. The simple yet inquisitive melody lands somewhere between pop and modern classical while the nimble orchestration subtly weaves in and out of the background. What’s played carries as much weight as what isn’t played, while the enigmatic lyrics (“is that my name on the bell?”) conjure up themes of mortality and the meaning of existence.

“Wrapped In Grey” also opens with piano, the chords this time straight out of the Bacharach/David songbook. Accompanying orchestration soon follows, while Partridge tenderly sings of how “Some folks see the world as a stone / concrete daubed in dull monotone.” He likens one’s heart to a “big box of paints” and references “the canvas we’re dealt.” After the first verse, the instrumentation takes over, only briefly, until the music suddenly rises, the chords changing from minor to major and the whole song soaring on a magisterial chorus that concludes with Partridge urging, “Don’t let the loveless ones sell you a world wrapped in grey.” This most moving and wise song is where Partridge ceases paying tribute to Brian Wilson and turns out something as powerful and unique as anything the latter ever did, especially when the song ends on an unexpectedly playful ascending coda.

Portions of Nonsuch displayed such intriguing artistic growth that most fans could hardly wait to see what XTC would do next. Unfortunately, that wait extended to seven years because of a stalemate between the band and its record label. Apple Venus (1999) encouragingly built on Nonsuch’s most innovative advances, utilizing palettes both orchestral (“Easter Theatre”) and acoustic (“Knights In Shining Karma”). If the electric guitar-heavy Wasp Star (2000) was less consistent, it still carried a handful of gems (“Stupidly Happy”, “The Wheel and The Maypole”) that would be career highlights for scores of lesser bands. Regrettably, XTC disintegrated as multi-instrumentalist Dave Gregory quit in the middle of recording Apple Venus and Moulding stopped returning Partridge’s calls in the early 00’s. And as much as I wish Partridge would get it together and record a proper solo pop record, I am content with the dozen or so albums XTC left behind. They are a band ripe for rediscovery, a bedroom Beatles, a post-punk Kinks, cult artists who often lived up to their popular influences and occasionally transcended them.

Up next: Redemption via compilation.

“Wrapped In Grey”:

“My Bird Performs”: