Despite their ubiquity, movies sequels rarely match their predecessors and almost never better them. Critics and fans alike may go to bat for The Godfather, Part II as the superior entry in that trilogy (I finally saw it last year—surely the gold standard for what a sequel should be, but I still prefer The Godfather) and The Empire Strikes Back arguably refines and deepens the universe introduced in Star Wars, as does Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2 for its previous entry. Still, most sequels fall short if just by a hair (Austin Powers: The Spy That Shagged Me) or more often, a country mile (City Slickers 2: The Legend of Curly’s Gold, anyone?)

Even arthouse cinema is not immune, though its filmmakers may try dressing up their sequels in other guises. Francois Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel series revisits the same character (played by Jean-Pierre Leaud) five times over two decades though The 400 Blows, which introduces him is so widely revered (deservedly so, since it’s more or less ground zero for the French New Wave) one can imagine only the most contrarian critic wasting the effort to extol Stolen Kisses or Love On The Run in favor of it. The most successful sequels are often stumbled upon for artistic rather than commercial reasons, like Abbas Kiarostami’s Life, and Nothing More… where he dramatizes seeking out the child actors from his earlier film Where Is My Friend’s Home following an earthquake ravaging the remote village where it was shot. Rather than feeling forced, it’s a meta-commentary on how life and art intersect more than a continuation of its story.

After The Godfather Part II won six Academy Awards (three more than The Godfather) and Airport 1975 became the seventh highest grossing film of its year, the floodgates opened: now, multiple sequels to such blockbusters as Jaws and Rocky were not only inevitable but also practically expected. If anything, sequel-itis has spread exponentially in the 21stcentury (see the Marvel Cinematic Universe among other mega-franchises) to the point where it’s hardly worth getting worked up at a multiplex sign where a majority of the films screening have a “2”, “3” or an “X” after their titles. Artful or not, they’re here to stay which is why in 2004, that year of Spider-Man 2, Shrek 2 and the more creatively titled Meet The Fockers (the only creative thing about it, really), I was skeptical when I first heard of Before Sunset, a sequel to Before Sunrise from nine years before reuniting director Richard Linklater with actors Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy. In the earlier film, American Jesse (Hawke) and French Celine (Delpy) meet on a train travelling across Austria and impulsively spend 24 hours together walking around Vienna before each of them must return to their native countries. A wistful, short-term romance with the loquaciousness of an Eric Rohmer film (perhaps crossed with one of Billy Wilder’s less satirical efforts), it did what it set out to do fully and enchantingly thanks to its stars’ innate chemistry and Linklater’s characteristic humaneness and nimble, attentive camerawork. With such a perfectly executed film, why try to recapture that seemingly once-in-a-lifetime magic again?

What immediately sets Before Sunset apart from other sequels is that it never resembles a cash-grab or a product its creators felt obligated to make, even if Before Sunrise was widely beloved and a modest hit. Linklater, Delpy and Hawke (all of them contributing to the screenplay) began working on a larger-budgeted sequel (with locations in four countries!) shortly after the first film came out but failed to secure funding. They only resumed work on it in 2003 albeit at a much smaller scale. One can easily comprehend the desire to revisit Jesse and Celine a decade (or even a year or two) after their passing meet-cute but to actually make good on that challenge and create something that recaptures the essence and insight of the original is a tall order. Happily, if nearly improbably, Before Sunset not only accomplishes this but ends up one of the rare sequels that arguably improves upon its predecessor, retaining its spirit while also extending its narrative in ways that feel less like a rehash than a reunion gradually revealing itself as a reassessment: what would it be like for Jesse and Celine to meet again and more importantly, what would that mean for them?

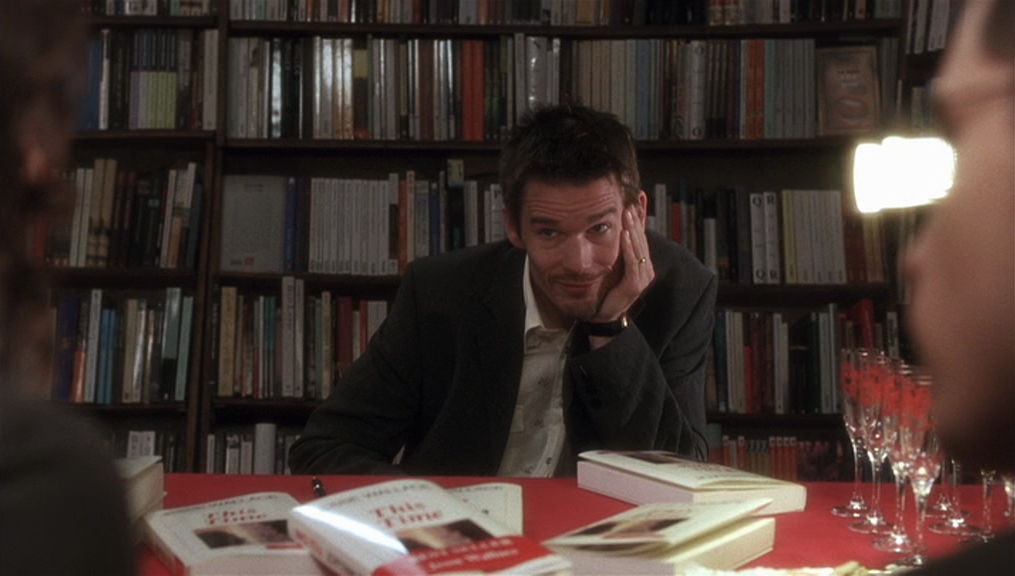

As previously noted, Before Sunset picks up nine years after that chance meeting on a train in Austria. The new setting is Paris and Jesse is on the last stop of a European tour for his first novel, This Time, a roman à clef inspired by his whirlwind romance with Celine. During the Q&A portion after his reading at famed English language bookstore Shakespeare and Company, he spots Celine herself standing near the back of the audience. Unlike the earlier film, her presence here is not random; she’s there (in the city where she resides) to purposely see Jesse read from his book about their fling. The moment he and the audience become aware of her presence carries a jolt of recognition which Hawke, often a more subtle actor than he’s given credit for conveys beautifully. As they say hello and embrace, one can detect an instant spark but also the hesitancy one would expect from a situation orchestrated by one participant and unexpected by the other.

Jesse has a plane to catch, leaving him and Celine with barely an hour to spend together. As they did in Before Sunrise’s Vienna, they walk through the streets of Paris, stopping in a café here, a park there, getting caught up and getting to know each other (again) as their dynamic and particular rhythms gradually fall back into place. Celine, however, now has a hometown advantage, directing where the two them will go. As they catch up, they each reveal more about themselves than they might initially mean to. They answer whether either of them made good on their parting pact of showing up at the Vienna train platform six months after their first meeting (Jesse did, Celine didn’t—she was at her grandmother’s funeral.) They also debate on whether they had sex (off camera) in the Vienna park (Jesse argues that they did twice; Celine doesn’t recall it, positing, “Memory is a wonderful thing if you don’t have to deal with the past.”)

All the while, the question “Does anyone change?” lingers in their pauses between conservation; as much as either one would like to deny it, their body language often says otherwise: at different times, one of them tentatively reaches out to touch or comfort the other, only to pull away, sensing the recuperations of such a gesture. They may be recognizable as the Jesse and Celine of the first film, but they’re also noticeably older (especially early on when Linklater silently cuts back to brief shots from the first film) and also perhaps… wiser? Now an environmental activist, Celine’s as impassioned as her younger self, but more caustic, a little angrier and maybe a bit jaded. Jesse, who is married and has a young child is still something of a wanderer/dreamer but he carries with him a newfound pragmatism and stronger sense of maturity compared to his younger self.

Eventually, catching up and small talk gives way to abrupt, messy emotional disclosures. Midway through, Jesse can’t help but moan in resentment and regret at Celine not showing up again in Vienna while she later snaps at him, “I was fine until I read your fucking book!” They each muse on what might have been, realizing that for a small period they both lived in New York City at the same time but never ran into each other (or even sought each other out.) Jesse confesses that his marriage is falling apart (perhaps inspired by Hawke’s then-recent divorce from Uma Thurman) while Celine considers their past, referring to it as “That moment in time that is forever gone.” All the while, tension mounts for the clock is running out—Jesse still has that plane to catch, a fact both of them repeatedly acknowledge, recalculating what diminishing amount of time they have left while also figuring out ways to prolong it. After they hug each other for a presumably final time, Jesse asks his car service to the airport to instead drive him and Celine to her apartment. He then walks her through the building’s vast courtyard to her front door. She invites him inside for a cup of tea; he accepts.

Before Sunset might be one of the most suspenseful romances ever made because it plays out in real time: its eighty minutes covers that exact, unbroken period in the lives of these characters. As much a narrative-driver as the single day was in Before Sunrise, this duration almost feels as if time itself has collapsed since we’re not used to seeing it play out so meticulously. Even more so than the earlier film, this one is composed of long takes as the camera follows and tracks Jesse and Celine’s journey (the late-in-the-day sun-kissed cityscapes add to the overall allure.) Their temporal space, by being fully synced up with our own creates an intense, almost unbearable sense of intimacy, like we’re right there with them accompanying their every move. By the time Jesse and Celine are slowly walking up the stairs to her apartment, the tension is off the charts—it’s exhilarating to watch them take each step wondering how much further they will go together. Actually, how much further can they take this? Jesse still has a plane to catch! (Not to mention a family waiting for him back in America.)

Once inside Celine’s exquisitely bohemian apartment, he asks her to play one tune for him on acoustic guitar (she earlier mentioned that she had been writing songs as a hobby.) She chooses “A Waltz For A Night” which is her side of their story, a three-minute folk/pop song equivalent to Jesse’s novel. Breathily, lovingly, she sings, “I just want another try, I just want another night” before almost coyly adding, “One single night with you, little Jesse / is worth a thousand with anybody,” (the cut to Hawke’s face when she sings “Jesse” is as startled and ebullient as his first view of her at the bookstore.) She makes tea, he puts on a Nina Simone CD. She tells him of when she saw Simone in concert before her death, swaying like her to the music. She says to him, “Baby, you’re going to miss that plane.” He responds, “I know.” No reasonable viewer can wait to see what happens next but wait they must, for the screen fades to black and the end credits roll. When I first saw the film in a theater, the audience let out a reaction that was equal parts relief, bemusement and slight frustration at this ending, but it’s perfection in how it exhibits grace and restraint after all that wish fulfillment tempered by built-up and sustained stimulation and uncertainty. Sure, it could’ve been satisfying to see Jesse and Celine kiss or embrace but here, just the process of their reconnection and how witnessing it playing out in real time makes it feel earned provides what’s needed for their arc to resonate.

I rewatched Before Sunset a year later in a theater as part of a double feature with Before Sunrise but didn’t view it again for another nine years (coincidentally, the same period of time separating the two films.) Now past the age of Celine and Jesse in Before Sunset, the film hit me even harder: that slooow walk up the stairs proved more effective, even when knowing what would happen next. The intimacy established between the two leads was rare in that it seemed to come from a real place rather than a storybook construction. I wanted Jesse and Celine to be together, I saw that they wanted it too but I didn’t know if it would be just for a night or longer than that or even at all. This notion remained true to the spirit of Before Sunrise while enticingly pushing it further—I was offered another mere glimpse into the lives of these two people but this time, the possibilities seemed limitless as the spark was reignited.

Nearly two decades on, as sequels go, Before Sunset remains an anomaly more than a precedent. Some recent film sequels are perfectly respectable: The Incredibles 2, Paddington 2, the John Wick films (haven’t seen any but I suspect many would argue for them.) Once in a blue moon, one will emerge that’s arguably stronger as its predecessor (Cedric Klapisch’s Russian Dolls, which I remember liking more than L’Auberge Espagnole.) However, most sequels still suck or are at the very least an inferior product.

Thus, Linklater, Delpy and Hawke faced a unique challenge when they decided to revisit Jesse and Celine another nine years on in Before Midnight. Without spoiling too much, the film drops in on another specific and brief period of time in the characters’ lives, gradually revealing all that has happened since the ambiguous ending of Before Sunset. It is a thornier film by design, going deep into how time influences perception of self and others and what consequences such familiarity portends. The tone is much different from the first two films without losing sight of who the characters are or obscuring their spirit—there are still lengthy conversations and an exotic setting but also an acknowledgement of early middle-age as a period fully distinct from one’s early thirties or twenties. It also ends on an ambiguous note that could easily serve as an invitation for another sequel or a conclusion.

Although Delpy nixed the idea of a fourth film in 2021 (nine years after the production of Before Midnight), a year later Hawke suggested the potential is still there for the three principals to come together and continue the story. I liked Before Midnight but wouldn’t rate it as highly as Before Sunset—something about the latter’s unexpectedness added so much to its appeal. For a fourth film (maybe After Sunrise?) to work, Linklater, Delpy and Hawke would need to be in sync with an inspired idea that builds on the previous entries, favoring a deepening of the story and not serving as mere fan service. Before Sunset did that brilliantly and as long as sequels aren’t going away, more filmmakers should study it.

Essay #15 of 24 Frames.

Go back to #14: What Time Is It There?

Go ahead to #16: Me And You And Everyone We Know.