Will be posting some old essays from former blogs of mine over the next few weeks as I take a hiatus from new writing; this piece was fun to revisit two decades on.

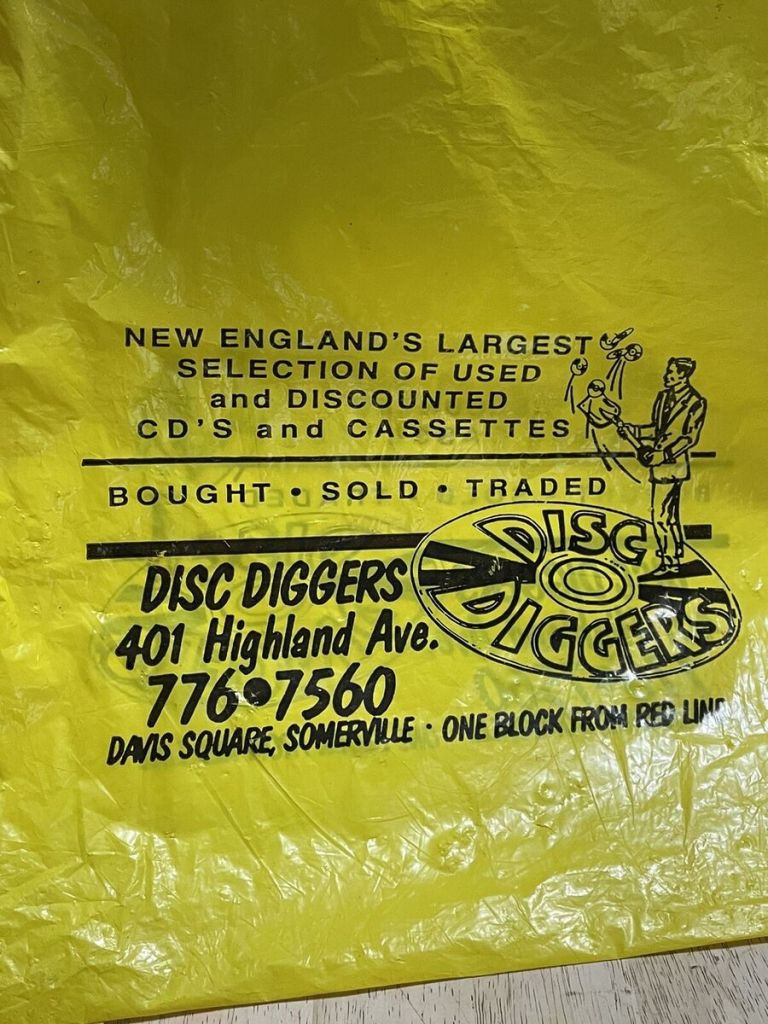

On January 1, 2005, another used-record store bit the dust: Disc Diggers in Davis Square, Somerville, Mass. While never my favorite recycled music shop, I’d pop in once every couple of months (grudgingly handing over my backpack to someone behind the counter) and occasionally find just what I was looking for.

I made my last Disc Diggers purchase on the last Saturday of the previous September. I had taken my bike across town on the T to ride the Minuteman Trail from Alewife Station to Bedford Depot and back. Exhausted and sweaty, I entered the store thinking, “OK, I’ll only buy something if they have Sally Timms’ In the World of Him or Tegan and Sara’s So Jealous.” When I spotted the former after running my fingers through racks and racks of new releases, dust-covered castaways and pitiable also-rans, I felt a rush of adrenalin–maybe not enough to take another ride on the Minuteman, but a sufficient reminder as to why I obsessively rummaged through one used-record store after another. It’s not just the goal of finding that particular CD I didn’t want to pay full price for or potentially unearth a buried treasure that could change my life. The challenge, the chase, the pursuit was just as essential.

The prototypical used-record store straight out of Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity endured for decades. I wasn’t aware of them until I turned eighteen. That year, CD Exchange, a three-store chain opened in the Milwaukee suburbs. As the name suggested, they didn’t traffic in vinyl or cassettes. The whole concept was foreign and questionable to me–selling CDs you no longer wanted… and buying other CDs someone no longer wanted… and hearing them right there in the store, at one of eight personal listening stations! It seemed too good to be true, and I approached the establishment with timid adolescent caution. However, the burgeoning bargain hunter in me (spurred on by working at a detestable, low-wage food service job) soon conceded, and I eventually made the rounds at the CD Exchange near Southridge Mall more often than Best Buy or local indie chain The Exclusive Company.

Alas, CD Exchange was an anomaly, a young upstart, a business perfectly suited for a mini-mall; nothing at all like Second Hand Tunes, my first real used-record store. Nestled on the corner of Murray and Thomas in Milwaukee’s East Side (and technically part of a chain that included a few Chicago locations), it was exactly like the store in High Fidelity only smaller, more condensed. At both windows sat wooden bins jammed with rows of plastic slipcases holding hundreds (thousands?) of CD booklets–all discs were kept behind the counter to discourage/prevent shoplifting. Tall, vertical see-through cases of cassette tapes made up the elevated employee counter at the other two ends of the square-shaped room, and in the store’s center, a giant, double-decker, C-shaped bin held most of the vinyl. Naturally, the windows and walls were plastered with cultish film and music posters of the Jimi Hendrix/A Clockwork Orange variety.

I spent many a Saturday afternoon in the mid-90s at that place, often flipping through every last slipcase, picking up used copies of stuff like They Might Be Giants’ Apollo 18, The Clash’s London Calling, and the Dukes of Stratosphear’s Chips From the Chocolate Fireball. Given their immense selection and my tenacity and dedication, I always found at least one thing to buy, if not two or five. I regularly saw guys (customers at these places were predominantly male) with teetering stacks of fifteen or twenty discs in their hands, and I couldn’t imagine getting together the funds to make such a weighty purchase.

Before long, I began thumbing through the neglected dollar vinyl that sat in a wooden crate on the floor beneath the CDs. At that point, it had been four or five years since you could find any vinyl in most new record stores. At the height of my wannabe urban hipster phase, vinyl was uncool in most mainstream circles, thus cool to me. I loved the comparatively life-sized cover art and the cheap thrill of picking up something I’d been secretly itching to hear (like Missing Persons’ Spring Session M) for only a buck.

I acquired a cheap-ass table-top stereo with turntable and amassed a collection of about 50 or so vinyl records with a year. I drove all over the city and the outlying ‘burbs, habitually visiting likeminded businesses such as Rush-Mor, Prospect Music and national chain Half-Price Books (they sold music, too.) Between that and continuing to buy new CDs at the big stores and through at least three of those “Buy 12 CDs for the price of one!” deals you used to always find inserted in Rolling Stone, for the first time in my life, I had more stuff to listen to than I knew what to do with.

Whenever people ask me (sometimes contemptuously) how in the world I’ve ever heard of band X or know of singer Y, I guess this partially explains how I became such a music geek. Kinda like a chain reaction, really: you discover something you like, and then it encourages you to check out something else (or, if you’re as fervent as I am, five or ten other things) and so on.

I had nearly as much difficulty leaving Second Hand Tunes behind as I did my family and friends when I moved to Boston in 1997. You’d expect to find an adequate replacement in every other neighborhood in the most college-friendly metropolis on the East Coast, but I’m not sure I fully did. The closest I came was Record Hog, a triangular corner shop steps away from the Cambridge/Somerville town line near Porter Square. They didn’t carry cassette tapes (by 1999, precious few places did) but everything else was perfectly, warmly familiar. More often than not, two cats sprawled their lazy selves across the centerpiece CD case and you’d have to gently lift them off the row of the discs you wanted to look through. This was where I made my greatest on-a-whim purchase ever (Ivy’s Apartment Life), in addition to fabulous buys like a promo copy of Stew’s The Naked Dutch Painter… and Other Songs (stumbled upon a week before you could buy it at Newbury Comics!), Gordon Gano’s Hitting the Ground and Bellavista Terrace: The Best of the Go-Betweens, among many others.

Alas, Record Hog closed in early 2003 and supposedly moved to a small town in Western Mass (I can’t remember which town and a Google search for “Record Hog” brings up little but costly pork prices). I continued acquiring a lot of used CDs every year, most of them from the local chain CD Spins, a true successor to CD Exchange. In each location, discs literally lined the walls from ceiling to floor. A CD Spins visit more or less satisfied my used-music jones, but it was like trying to get high off a pack of Marlboro Lights. I couldn’t possibly ever take in each store’s massive stock at once (at least half of it obscure $1.99 crap), so I skimmed through a mental list of stuff I’d like to get, which made it shopping with a goal in mind instead of a free-form stress-relieving act of discovery. A few used-music establishments with potential still lurked within various corners of Boston and Cambridge (and a handful even carried vinyl), but most of them were either too expensive or limited in their selection.

My last visit to Second Hand Tunes was in October 2000. In town briefly for a friend’s wedding, I had an extra day to visit a few hangouts that were once so dear to me: Kopp’s Frozen Custard, Klode Park in Whitefish Bay, and Second Hand Tunes. I hadn’t set foot in the store in more than two years and was surprised to find it haphazardly rearranged. The discs sat where the vinyl used to be, and they now even carried DVDs. Two employees I didn’t know talked loudly to each other behind the counter, watching clips of a training video for the Bronx police department. I made a customary run through the slipcases, briefly considered purchasing Bebel Gilberto’s Tanto Tempo, and then left without doing so. On my next trip two years later, the windows were papered up and a pitiful “Office Space for Lease” sign sat in one of them. Around the time I moved out East, one of the store’s old managers opened up his own used-vinyl/CD haven two blocks away. I made an effort to visit it every time I was back in town.

I missed Second Hand Tunes, Record Hog and all the rest. I no longer bought vinyl but still had enough disposable income to justify the hours I spent feeding my used CD fix. I wasn’t against buying music on Amazon or iTunes, although I knew that to an extent, both were doing their part to put the oldfangled High Fidelity stores out of business. I’d just about given up on finding a replacement that captured the personable, homey feel of those places. Thankfully, none of that distracted from the pleasure I still received from a newly acquired album, particularly one that resonated on the first spin.

2025 POSTSCRIPT:

Most remaining used CD stores went kaputt in the five-to-ten years after I wrote the above essay. I’ll never forget a depressing visit to an on-its-last-legs CD Spins which seemed packed to the gills with dozens of copies of the same, unloved used product, a far cry from when I spotted a rare copy of the import-only The Misadventures of Saint Etienne for thirteen bucks there a few months after posting this piece. Overall, I dealt with the demise of used CDs miserably, reduced to downloading entire albums from iTunes, patiently awaiting the convenience (if not the same sort of thrill) that streaming music would provide.

I certainly did not see the vinyl revival coming. By late 2016, I said fuck it and purchased an affordable but not cheap-sounding Audio-Technica turntable, hooked it up to my Bose stereo (with CD player!) and learned to love vinyl again—not always an affordable pastime in its own right (especially given the hike in pricing since Covid). Fortunately, it does scratch that music-purchasing itch, especially at such fine stores as Sonic Boom in Toronto, Irving Place Records in Milwaukee (owned by a former associate of the guy who managed Second Hand Tunes) and Lost Padre Records in Santa Fe, where on a visit in 2023 I picked up used, reasonably-priced vinyl copies of both the Starstruck soundtrack and Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants.