On March 13, 2020, the new film First Cow both opened and closed in Boston, where I worked at a non-profit arthouse theatre that screened it. As was my custom on Friday afternoons, I snuck away from my desk to catch the 2:00 show. I suspected it might be my last chance to see it for a while (at least in a cinema); my fears were affirmed directly afterwards when, over a conference call with other staff and a few board members, we decided to shut down operations as of 6:00 that evening with the intent of possibly reopening by month’s end. This meant First Cow would receive one more screening, the last of three overall—the shortest theatrical “run” I can ever recall at this theatre. What was an anticipated and buzzed-about release of the latest feature from acclaimed independent director Kelly Reichardt ended up almost entirely derailed by COVID-19.

Over the next few weeks, then months, I was increasingly grateful for seeing First Cow when I did—not only for the opportunity to do so theatrically but also in that it was the last cinema screening I would attend for another eighteen months. At the time, I didn’t know that one of my favorite leisure activities would be involuntarily put on hold for so long. In the past two decades, I had watched an average of 75-100 movies in cinemas per year (working at one made this convenient), sometimes more (126 in 2005!). The only time I went more than a week or two without going to the movies was the month I got married and honeymooned in Santa Fe in 2013. Filmgoing was but one of many things the pandemic abruptly changed.

Upon lockdown, I was initially thrilled with all that extra time to catch up on movies at home (along with the privilege of working my mostly administrative job remotely.) With streaming more dominant than ever, I had no (and four+ years later, still have no) shortage of films to pick from. I made a watchlist that I’ve added to and checked off from ever since and used the two+ extra hours in my day (reclaimed from my back-and-forth commute) to begin a valiant but ultimately impossible task in whittling it down.

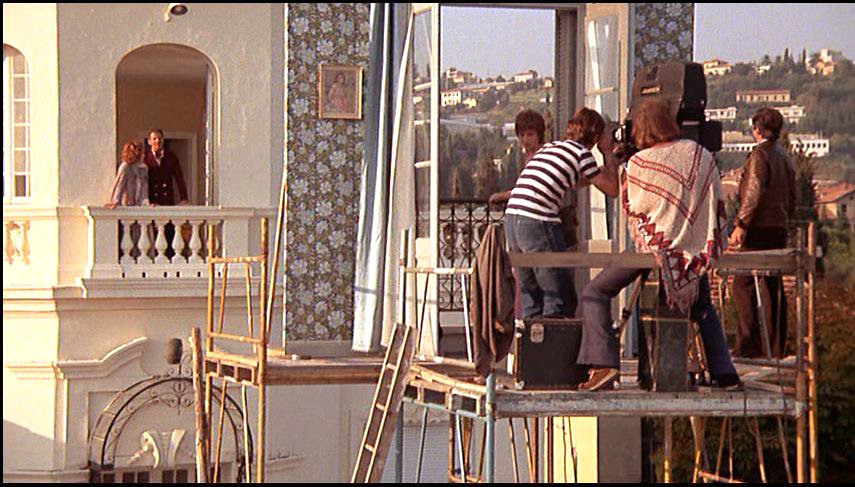

During those first weeks, I caught up on classics I hadn’t seen (Atlantic City, A Place In The Sun, Czech surrealist piece Daisies) and revisited other ones for the first time in decades (The Swimmer, now resonating more with me after having absorbed seven seasons of Mad Men.) I watched a few relatively recent titles (Mississippi Grind, which I dug and Hale County This Morning This Evening, which I found a slog) and others that I’d been meaning to check out such as The Myth of The American Sleepover (David Robert Mitchell’s pre-It Follows feature), The Last Waltz (I can still picture Van Morrison’s sparkly outfit!), Le Bonheur (an early Agnes Varda narrative that’s nearly as essential as Cleo From 5 To 7) and Day For Night, whose making-of-a-movie narrative struck a deep chord and encouraged me to check out other Francois Truffaut films I had missed (including, eventually, the entire Antoine Doinel cycle post-The 400 Blows.)

By mid-April, it was obvious lockdown wasn’t going away anytime soon. I began anticipating the first of each month mostly to see what new titles had been added to The Criterion Channel (along with what would expire at the end of said month, prioritizing my watchlist so as not to miss anything.) I’d leap from genre to era depending on what was available and what struck my fancy on a particular day. I fell in love with first-time watches like It’s Always Fair Weather, Private Life, High and Low and The Best Years of Our Lives. I revisited comfort food favorites such as Waiting For Guffman, Moonrise Kingdom and The Out-of-Towners (original Lemmon/Dennis recipe) and headier stuff such as My Own Private Idaho, Derek Jarman’s The Garden and Scenes From a Marriage (Bergman version, naturally.) I’d devour curated series on Criterion such as early Martin Scorsese shorts (Italianamerican a must-see for anyone who adored him mom in Goodfellas), Abbas Kiarostami’s “Koker Trilogy” and Atom Egoyan’s pre-The Sweet Hereafter oeuvre, which I hadn’t watched since the late 90s.

Hopes of my theatre reopening to the public came and went after Christopher Nolan’s Tenet was indefinitely delayed. Gradually, titles that would’ve normally received theatrical releases began showing up directly on streaming services. I watched Josephine Decker’s Shirley the Friday in June it premiered trying to convince myself it was like one of those long-missed opening day shows I’d often attend at work. Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods and Charlie Kaufman’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things followed (even if both were on Netflix where a theatrical release would’ve been limited anyway.) Theatres like mine learned to pivot, providing content for viewers to rent online as did film festivals such as PIFF, where I watched Black Bear (still Aubrey Plaza’s greatest film performance to date) and TIFF, which I was able to procure an industry pass for from work, seeing over 20 titles, Nomadland, Shiva Baby and Another Round among them.

Near summer’s end, a good friend from my film group emailed our discussion list; planning on watching one of these new video-on-demand titles, she asked if we wanted to do the same and then discuss it on Zoom. The movie in question, paranormal love story Burning Ghost was laughingly bad but it did kick off a weekly tradition that endures to this day. Happily, subsequent film picks were far better: South Korean coming-of-age drama House of Hummingbird, low-budget but visionary sci-fi The Vast of Night, ultra-indie gambling thriller Major Arcana and Bas Devos’ lovely work of slow cinema, Ghost Tropic (which could not have been further from Burning Ghost, aesthetically or quality-wise.)

About a month-and-a-half in, we saw a film that has stuck with me arguably longer than any other titles mentioned in the last paragraph. Ham On Rye, the debut feature from writer/director Tyler Taormina was now available to stream through the Brattle Theatre’s VOD service (dubbed “The Brattlite”.) Despite having played the festival circuit in the months leading up to lockdown, it was unfamiliar to me (perhaps IFFBoston might’ve screened it that April.) It had a unique title and intriguing promotional art, however, along with some comparisons to Richard Linklater and David Lynch.

Although filmed in the San Fernando Valley section of Los Angeles, the first half-hour could take place in any sun-drenched idyllic suburb. After a pre-credits sequence of abstract close-ups occurring at some sort of family picnic in a park (such as a handheld sparkler’s fuse burning out right after ignition), Ham On Rye resembles an ongoing, somewhat rambling montage of various teenagers doing ordinary things: painting their nails, pulling up their socks, lifting weights and cruising through neighborhoods blasting music (from classic soul to headbanging power-pop) from their car stereos.

Gradually, it shifts into focus that these kids are all in one way or another preparing for some kind of event that evening: a ritual not yet clearly defined for the viewer. Taormina inserts potential clues into nearly every scene: a group of girls gather together in long white dresses straight out of The Virgin Suicides while a gang of their male counterparts walk the streets decked out in mostly ill-fitting suits probably borrowed from their fathers. Maybe they’re all headed to a formal dance, like Prom? Whatever they’re anticipating, it’s still shrouded in mystery but also a Big Deal—when one kid gets picked up, heading off for the event, his dad fervently yells as the car pulls away, “Don’t mess it up! DON’T MESS IT UP!!!”

The grand destination in question for all these youth is soon revealed as Monty’s Deli (“relishing the moment since 1952” reads a sign on its front window.) Suddenly, the film’s title seems slightly less incongruous, although I’ll leave possible allusions to the Charles Bukowski tome of the same name to those more familiar with that literary work. Early on at Monty’s, there’s a jump cut of one of the boys signing some sort of official-looking contract to close-ups of various sandwiches, followed by a dining room exclusively populated by dressed up teens eating silently. Once the food is polished off, music appears (to my ears resembling a pastiche of The Association’s 1960s sunshine pop classic “Cherish”) and the kids get up to dance, again rather casually as if at a house party than anything like a formal event.

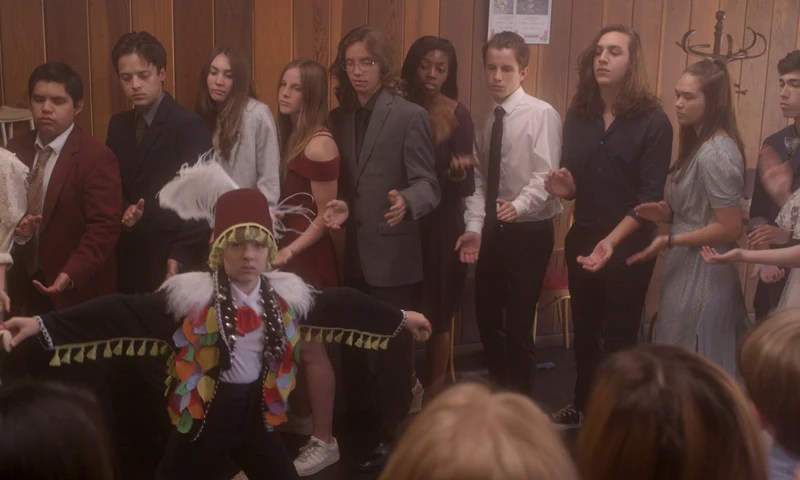

All of a sudden, the dramatic 1960s girl group sound of The Teardrops’ “Tonight I’m Going To Fall Again” (note the title) loudly begins and all the kids line up in a circle. Each person takes their turn stepping out of the circle and choosing someone by pointing at them. If the recipient offers them an upturned thumb, they go off and dance together. An array of rapidly edited up-turned and down-turned thumbs follows, heightening the tension. It’s all too much for Haley (one of the girls featured in the lead-up to this sequence), who abruptly breaks from the circle and runs out of the deli. Those not given an up-turned thumb are no longer allowed to participate. The chosen ones, however, remain as couples in the shared circle and begin a procession of sorts, clapping incessantly as a short kid wearing a fez and a modified matador-like costume leads the charge.

The mood turns joyful verging on manic, even as the couples fall into a slow dance and the deli becomes suffused with atmospheric lighting and colors that were nowhere to be seen when everyone was simply munching on their sandwiches. Then, a circle of gleaming, bright light appears above the chosen kids. Each couple kisses and the mood grows practically euphoric. The happy couples all leave the deli and blissfully walk down the middle of the street in the direction of the suburban enclaves from which they came. Gorgeously backlit in silhouette as twilight nears, one by one they begin vanishing into thin air! Hold on a minute—is this the rapture? What was in those sandwiches? (Also, is this similar to what happens to Mormons?)

This entire deli sequence is unquestionably the film’s climax, but it arrives at its exact midpoint—there’s another half-hour to go. Everything that follows is a comedown but by design as we spend time with all those left behind, like Haley, who can no longer reach her presumably raptured best friend by phone. Or the boy in the too-small suit whom we next see sharing a glum dinner with his mom at a fast-food joint. Or another kid who didn’t even make it to the deli because he accidentally fell into a pothole on the way there. A floppy-haired runt of a kid asks his fellow rejects, “Do I get a second chance?” and no one says a word as if to explain how numbingly obvious the answer is to such a question.

Even after the film reveals its “purpose”, it remains not entirely knowable. With an eye drawn towards liminal spaces and ambiguous imagery, Taormina not only relays a strange tale but does so rather unconventionally, favoring mood and texture over logic or any sense of narrative fulfillment. The film’s first half is one of anticipation but also dreamy reverie such as the sun-kissed lighting in nearly every shot and stylized touches like the folky, pan flute-heavy score accompanying the white-sheathed girls as they ride their scooters all around their verdant community. What comes after the deli sequence is relentlessly drab, a bit melancholy and often cloaked in darkness. We see the activities the unchosen partake in for what they are: simply unremarkable, such as a “rager” which consists of burnouts lounging around a campfire, swigging beer and dispassionately playing a hand of Uno.

Between these two poles, the deli sequence itself is a marvel. First encountering it six-plus months into lockdown, I got caught up in its sense of awe and mounting excitement unlike anything else I had recently seen. I didn’t really know exactly what I was watching as the couples vanished into nothing but I didn’t care, feeling nearly as blissed out as they appeared to be. The sobering aftermath for those who remained also resonated—it’s not much of a stretch to say it mirrored my own disappointment with no longer being able to do previously taken-for-granted activities such as, um, going out to the movies. I related all too well to this restlessness brought on by the despair of being stuck in limbo, unable to participate in life outside my house. Taormina could not have had any pandemic-specific ideas in mind when devising this film since it entirely preceded the whole shebang, but this hit differently for me than it might have had I seen it a year earlier.

Following Ham On Rye, our discussion group continued Zooming every week, coming together to dissect and debate more new-ish films like Kirsten Johnson’s meta-doc about her ailing father Dick Johnson is Dead, Miranda July’s typically, delightfully odd third feature Kajillionaire, and the meticulously edited and effective documentary Time. Outside the group, I found even more films to love both new (Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets; David Byrne’s American Utopia) and old (Claudia Weil’s pioneering indie Girlfriends; early Laura Dern vehicle Smooth Talk.) Taormina would follow Ham On Rye with a real pandemic project, the Long Island-shot, 62-minute tone poem Happer’s Comet and eventually, a second narrative feature, the forthcoming Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point.

As for me, at the end of 2020 I abruptly found myself unemployed for the first time in over 15 years. Naturally, I spent the first 90 days of 2021 watching (at least) 90 movies at home—through all of this previously unfathomable change, films remained my refuge, my constant, my church. None of us had any idea when or even if theatres would ever reopen; streaming and physical media would have to suffice until they did.

Essay #23 of 24 Frames

Go back to #22: Cemetery of Splendour

Go ahead to #24: Aftersun