Introducing 24 Frames, a new project where I write about movies—not necessarily my all-time favorites (although many of them will be) but those that had a significant impact on the way I watched and perceived movies in general. Aiming for a blend of film criticism and memoir with these, just as I occasionally did for music on 100 Albums. Essays will appear in chronological order of when I first viewed a film. Also, spoilers are guaranteed in each of these essays.

*****

Growing up, movies were just another leisure activity for me, as commonplace as walks in the park, visits to museums or Sunday drives out of the city. Going to “See a Show” (as my dad often called it) meant very little other than a social activity to partake in with friends and family until I hit my twenties.

Which is not to say I didn’t have any memorable childhood moviegoing experiences. From Disney’s Pinocchio, my first time in a cinema at age four (I have no actual memory of this, but my mom often mentioned it, never failing to note how scared I was) through roughly my early teens, like any good parents, my folks kept watch over what I saw. At ten, Back To The Future was entirely acceptable, even if the incest-leaning subplot between Marty and his mother was completely over my head (I did feel a little embarrassed watching with my parents the scene where Lea Thompson shows a bit of skin in the car with Michael J. Fox.)

Still, five years later, my mom forbid me to see the racy, R-rated Rob Lowe/James Spader thriller Bad Influence after my buddy Mike had won two tickets to it in a radio contest. By then, I was going out to the movies with friends instead of exclusively with my parents. Mike and I never tried to get into R-rated stuff, but we’d watch such things as The Addams Family or Joe Versus the Volcano (I rarely missed a Tom Hanks film in that post-Dragnet, pre-Philadelphia period) at pretty much the same places I went to see Harry and The Hendersons or Return To Oz with my parents a few years before.

However, I had to go beyond the local multiplexes or, in fact, any theater to stumble across a movie that, for the first time, expanded my idea of what one could be and also feel like it was somehow made just for me. This happened during a classmate’s birthday party at her split-level suburban home. It was less a “Sweet Sixteen” than a decidedly casual gathering—no getting-to-know-you icebreakers or games, just the usual opening of gifts, cutting of the cake and unfettered socializing.

After cake, the birthday girl wanted to watch a movie. Squealing with glee, she put her tape of Monty Python and The Holy Grail (which I’ll shorten to Holy Grail from here on) into the VCR. About twenty of us congregated into the family room as it began. I’d heard of but wasn’t too well versed in this old British comedy troupe, having watched Monty Python’s Flying Circus on MTV occasionally for a minute or two while flipping through channels.

I had no expectations when the film’s title first appeared in white on a black screen accompanied by a loud, dramatic minor chord on the soundtrack. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed the title again at the bottom of the screen in tiny letters. Something was off—it was in a foreign language which I didn’t yet recognize to be a sort of pidgin Swedish. This continued, unexplained for the next few frames of the credits roll, although it was soon obviously clear the subtitles weren’t matching up with their English counterparts. Under various crew member names, the subtitles consisted of such incongruities as, “Wi nøt trei a høliday in Sweden this yër?”and “Including the majestik møøse” (the latter under a string of credits arranged in the form a note erroneously “Signed RICHARD M. NIXON”.)

Then, the increasingly suspenseful score dwindled to a stop as if someone turned off the record player. Credits in a different font read, “We apologise for the fault in the subtitles. Those responsible have been sacked”; unfamiliar with that British colloquialism, I pictured someone getting hit in the head with a giant literal sack, not unlike the fake 16-ton weight that occasionally fell from the sky on characters on Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

The credits resumed, sans subtitles, seemingly normal until they definitely were not, becoming increasingly moose-centric: “Møøse trained to mix concrete and sign complicated insurance forms (by) JURGEN WIGG”, for instance. Soon enough, the score stopped again, followed by an additional insert informing us of more people getting sacked and a notice that “The credits have been completed in an entirely different style at great expense and at the last minute”—in this case, on a yellow flicker screen with celebratory Mariachi music, many mentions of llamas (including directorial credits to a few) and, at the very end, one at the bottom for the film’s actual directors (and Python members) Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones, kissed by a feisty “OLE!” on the soundtrack.

I had never before laughed so wildly at an opening credits sequence. It did what one was supposed to do while also frequently inciting total anarchy, not only spoofing the idea of mismatched subtitles but also breaking the so-called fourth wall, acting as if the credits were being constructed on the spot as the audience viewed them. Was the entire movie going to be like this? It certainly drew me in.

After a title card (ENGLAND, 932 A.D.) in a ridiculously ostentatious font, King Arthur (Graham Chapman) and his trusty assistant Patsy (Gilliam) arrive at a castle, not riding horses but banging two coconuts together to emulate the sound of their hooves (a solution to the expense and hassle of filming with actual horses.) The castle’s unnamed Lookout wonders where they had possibly found coconuts in England; it is suggested an African swallow could’ve carried them over and a back-and-forth ensues about swallows, their weight and air velocity, etc. Arthur and Patsy, bored, move on, coconuts at the ready.

Holy Grail initially feels like little more than a series of Medieval-centric sketches that could easily slot into the troupe’s TV show (which had aired its fourth and final season the same year.) A man (Eric Idle) strolls through a peasant village pushing his cart, collecting bodies (“Bring out yer dead!”) with a methodical nonchalance as if it were just an ordinary trash day. Arthur and Patsy briefly pass through and in the next scene, the former has an argument with an anachronistic, Marxism-spouting peasant (Michael Palin). They “ride” on into the forest and meet The Black Knight, who challenges Arthur’s authority with a duel, refusing to back down as the latter proceeds to hack off all his limbs. A line of marching, chanting monks methodically whack their own heads in unison with enormous books while Sir Bedevere (Jones) listens to an angry mob of men grasping at straws to prove that a young woman is actually a witch, to which Arthur joins the conversation.

It’s not until Bedevere and Arthur meet that the film’s narrative starts taking shape. We hear from an offscreen narrator about how they assemble the Knights of the Round Table (via a cutaway to “The Book of The Film”); following a brief musical interlude regarding the castle Camelot (done in the style of a rousing, Gilbert and Sullivan-esque number), a deliberately hastily-animated (by Gilliam) God appears from the heavens and informs Arthur and his knights of their heavenly quest, which is to find the film’s titular sacred object. From there, the episodic structure returns as knights individually split off to seek the Grail, only for them all to reunite in the final third to confront such obstacles as a killer rabbit, The Bridge of Death and a castle curiously guarded by some discourteous Frenchmen.

As with their TV show, Python loves a good running gag for the sake of a punchline and Holy Grail is chock full of them: numerous variations on the phrases “I’m not quite yet dead” and “I’m getting better!”; a fey Prince whom continually threatens to break into song, only for his father to plead to the camera to literally stop the swelling music; Arthur’s inability to count to three (substituting the word “five” only to be immediately corrected by one of his crew, “Three, sir!”); even the opening debate regarding swallows gets a callback when we first see Bedevere (attempting to release an actual swallow with a coconut tied to its leg), and later when it turns up the subject of one of the questions the Gatekeeper (Gilliam again) asks in order to allow passage over the Bridge of Death.

Motifs like these are common in comedies—just consult the work of Mel Brooks, whose Young Frankenstein, made around the same time as Holy Grail, features Gene Wilder’s titular character, an operatic tyrant not all that far removed from Chapman’s Arthur. But Holy Grail is more than just gags for the sake of being funny—as it goes on, it further deconstructs the very idea of itself, going all the way back to those opening credits. No matter how invested one becomes in the plot (and all the little side-plots) or the characters, the film keeps viewers aware that it’s only a movie (not unlike Patsy sniffing at Camelot in his sole line of dialogue, “It’s only a model”) and that none of it is real—a big risk for any movie to take considering it’s a medium that usually relies on an audience’s suspension of disbelief.

In addition to the aforementioned “The Book of The Film”, Holy Grail exhibits such self-awareness by referring to one sequence as “Scene 24” (I haven’t counted to see whether it actually is the 24th scene onscreen), stopping the action when a character pauses, looks at the camera as says, mid-scene, “Do you think this scene should’ve been cut?” (in fact, this part was cut and I didn’t see it reinstated until the film was first released on DVD) or an animated stretch where the cast is chased by a grotesque monster until the narrator tells us, “Suddenly, the animator suffered a fatal heart attack!” (cut to Gilliam drawing at his desk and quickly keeling over), continuing, “The cartoon peril was no more; the quest for the Holy Grail could continue.”

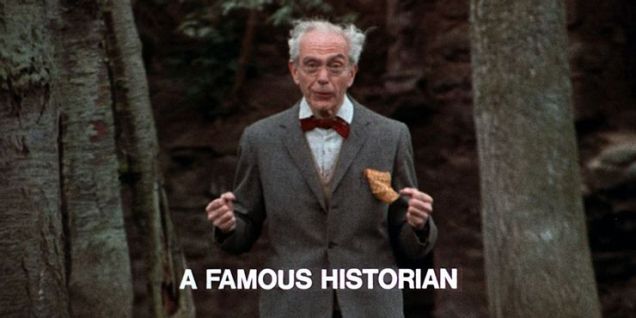

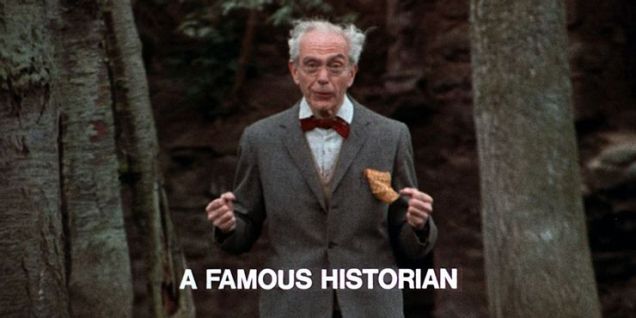

Holy Grail’s riskiest, most outlandish conceit arrives roughly a half-hour in when it cuts to an elderly man in contemporary scholarly clothes referred to as “A FAMOUS HISTORIAN.” As he excitedly lectures the camera about Arthur and the quest for the Grail, a knight on a horse (possibly Sir Lancelot (John Cleese)), face concealed gallops into the frame and slashes the poor sod’s throat, leaving the scene of the crime as quickly as he arrived. A grieving woman runs into the frame over to the slain body and cries out, “Frank!”

The film resumes as if this was just a silly aberration, but we’re far from done with the incident. About fifteen minutes pass before the grieving woman reappears along with two policeman, looking over the slain Frank. Later, the policemen and a detective, searching through the forest, overhear an explosion that is the killer rabbit getting obliterated by the Holy Hand Grenade. These dialogue-free scenes are so brief you might miss them; still, we know something is up late in the film when Arthur suddenly wonders where Lancelot has disappeared to and we cut to the latter arrested and detained, being searched as he stands, submissive, with his hands on a police car.

This strange counter-narrative doesn’t fully pay off until the final scene when, Arthur having assembled an army of hundreds (seemingly out of thin air) to storm a castle rumored to be holding the Grail, leads their charge only for the siren-blaring police car to cut them off. The grieving woman from earlier walks towards him and tells the police, “Yes, they’re the ones, I’m sure!” The detective leads Arthur into the back of a paddy wagon, a blanket put over his head. A policeman with a megaphone breaks up the more disappointed-than-disgruntled army and then implores the cameraman to stop filming (“Alright Sonny, that’s enough!”), putting his hand up against the lens. Everything goes white and then fades to black. Jaunty organ music plays on a blank screen for nearly three minutes. The End.

That first watch, I recall feeling more bewildered than disappointed at such an absurd ending. Admittedly, my attention had wavered in and out through the film’s duration; given its purposely episodic structure, I wonder if that was partially by design. I’d see it again six months later when it happened to air on a local UHF channel one evening. Of course, this broadcast was heavily edited for TV, not only cutting out naughty words and excessive gore, but changing the ending from a blank screen to a replay of the opening credits (at least the incongruous organ music was intact!) Eventually, Comedy Central would air a cut closer to the theatrical version that I’d watch again and again until the DVD arrived a decade later.

Even after I saw it numerous times, I still lazily dismissed the film’s ending, thinking it sort of… fell apart, not even making an effort to conclude its narrative in a satisfying way—just one of many unconventionally fun and different things about it. Even after earning a master’s degree in Film Studies, I clung to this opinion, and why not? To paraphrase Arthur’s concluding thoughts on Camelot after that whirlwind production number, “Holy Grail? It is a silly film.”

Of course, one of Monty Python’s greatest achievements was not only indulging in silliness but also taking it seriously—at least to the point before getting pretentious about it. While Holy Grail’s ending is not nearly one of the film’s funniest moments, it is one of its boldest. By allowing the modern day figures to not only intrude the action but literally bring the film to a close is a near-genius move. Think you’ve been watching a satirical goof about Medieval England? Well, how about something where a bunch of men film themselves dressed up as figures from Medieval England, assuming the roles of fictional characters, wreaking havoc, doing whatever they want until, after ninety minutes, they’re finally forced to stop?

The more one considers the implications of this, the more layers Holy Grail accumulates. One could think, “Yes, you’re watching a film. Of course, none of it’s real. Perhaps these people onscreen are delusional—this guy in the crown actually thinks he’s a King, the git!” And yet, such transparency doesn’t obscure the notion Holy Grail remains an entertaining comedy and an enjoyable spoof, not to mention a perfectly silly film.

While it took years for me to appreciate the movie and its ending on all of those levels, not long after that first viewing I did start taping Monty Python’s Flying Circus reruns whenever I could and eventually watched their other four feature films (I appreciated them all but have never felt as connected to any of them as Holy Grail); it also pointed the way towards humor more unconventional and intricate than what I previously knew, indirectly leading to Mystery Science Theater 3000, George Carlin’s stand-up and even old Beatles albums, whose wit and wordplay I hadn’t fully detected when I’d heard their hits on the radio as a kid.

Holy Grail didn’t turn me into a cineaste; on that first viewing, I responded more to the content than the form. But it was an early peak, an opening, a faint suggestion that movies offered much more than I had previously thought.

Essay #1 of 24 Frames.

Go ahead to #2: The Piano.