1. MAY DECEMBER

I suppose Todd Haynes’ latest does for Lifetime TV movies what his 2002 film Far From Heaven did for Douglas Sirk, recreating an aesthetic and carefully tweaking it for postmodern consumption; it’s also a study of what it means to perform or play a role, the self-awareness (or lack thereof) in doing so convincingly and the long-term implications of surrendering to one’s own delusions. Arguably only Todd Haynes (with help from Julianne Moore, Natalie Portman and Charles Melton) could pull off such a tricky balancing act, effortlessly blending camp and melodrama until they seem indistinguishable from one another. His most psychologically complex film since Carol (if not Safe).

2. ALL OF US STRANGERS

Andrew Haigh’s (Weekend) most ambitious, personal effort, a loose adaptation of a Japanese novel about a man (Andrew Scott) confronting his past in an unusual way (to say the very least in avoiding spoilers here.) With great work from Scott, Paul Mescal, Jamie Bell and Claire Foy, Haigh utilizes a visual and sonic language that feels singular in its focus and drive. Call it a sci-fi tinged, queer mid-life crisis film or a less solipsistic companion to, say, Call Me By Your Name but note the key lyric from a Frankie Goes To Hollywood song (one piece of a brilliant soundtrack) emphasized here: “Make love your goal.”

3. THE HOLDOVERS

This return to smart, dyspeptic comedy reunites director Alexander Payne with another master of the form, Paul Giamatti. Not only set in 1970, it also looks and feels like something from that period with its painstakingly correct stylistic touches (opening credits font, slow dissolves, winsome folk-rock soundtrack), fully capturing the feeling and substance of a good Hal Ashby film. Still, Giamatti (an ornery all-boys schoolteacher), Da’Vine Joy Randolph (a cafeteria manager whose son was recently killed in Vietnam) and newcomer Dominic Sessa (the belligerent pupil Giamatti’s tasked to look after during holiday break) together give the film its soul.

4. MONSTER

The first third of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s first effort set in his native Japan since Shoplifters comes off as a darkly comic fable about a fifth-grader being bullied by his teacher; what happens next sets the momentum for a narrative only fully revealed one all of its pieces gradually fall into place. One of the director’s most accessible works due in part to its swift pace, the unique structure enhances its rhythms—it also clinches one’s attention with humor and a tricky premise but then extends an invitation to learn the full story and witness how we can instill change in one another.

5. SHOWING UP

Kelly Reichardt’s (First Cow) latest is a reminder as to why I admire films where, while viewing them, my perception slowly, organically shifts from “Why am I watching this?” to “I never want it to end”. I’m also drawn to those that delve into the notion that it’s always best to go with the flow. Naturally, Reichardt’s longtime collaborator Michelle Williams is perfectly cast (as a somewhat cranky but undeniably talented starving artist), but don’t forget Hong Chau once again killing it in a supporting role or the evocative sound design.

6. AFIRE

This might be Christian Petzold’s (Undine) most explicitly comedic film to date. It starts off unassumingly, slowly building its relationships and character arcs as wildfires remain a background threat heard about but only seen via glowing, burnished, distant skies. Like those fires, it’s a slow burn until, all at once, it encompasses everything in its path with dire consequences for some and narrow escapes for others. It’s reminiscent of a Gary Shteyngart novel in that it’s expertly constructed, caustically funny and in the end, tinged with tragedy and the possibility of transformation.

7. GIVE ME PITY!

Cheerfully billed as “A Saturday Night Television Special” starring Sissy St. Claire (Sophie von Haselberg), writer/director Amanda Kramer’s art piece may feel as if it’s beaming in from another planet to those unfamiliar with 1970s/80s variety shows. But she understands that if you’re going to make a feature-length pastiche, pinpoint accuracy is required (smeary video in the 4:3 standard definition format, elaborate wigs, neon colors, the requisite hanging mirrorball, vintage-looking graphics, etc.) It also gradually transcends its premise, peeling off layer after layer of everything that goes into a performance and the toll it can take on the performer’s psyche.

8. PAST LIVES

One can easily detect why Celine Song’s debut feature was so celebrated this year. In addition to strong performances from Greta Lee, Teo Yoo and John Magaro, it presents a love triangle setup with rare subtlety: it conveys its dramatic intricacies with grace and an understanding of what it means to be here now, always and forever one of the most relevant personal conflicts that narrative films tend to gloss over or simply ignore. It’s also invaluable as a record of how the present and past began to converge in the age of social media.

9. RYE LANE

British writer-director Raine Allen-Miller’s widely praised debut feature has all the elements a good rom-com should (sharp screenplay, appealing leads w/chemistry, plenty of laughs) but also an actual perspective that’s deeply felt in everything from the visual design and location shooting (South London comes off as vibrant here as it did dystopian in All Of Us Strangers) to the way in which it coaxes and earns its laughs. Acquired by Hulu in the US, it should have had as robust and expansive a theatrical release as Past Lives.

10. ANATOMY OF A FALL

A thriller about a woman (Sandra Hüller) accused of her husband’s murder that could just as easily have been a suicide, Justine Triet’s Cannes Palme d’Or winner is nearly as suspenseful as the best Hitchcock while also considerably more humanist in its depictions of the main character and her son. The trial scenes can be a bit much (e.g. the smug prosecutor) but overall this plays like a riveting page-turner of a novel. As the hearing-impaired son, Milo Machado Graner gives the best child performance in eons next to Lola Campbell (Scrapper).

11. KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

Between the lead performances (Lily Gladstone, we love you) and how masterfully it builds without coming off as awards-bait, this already feels like Scorsese’s best of this century.

12. CLOSE

So much here is communicated through facial expressions and pauses in conversations. Explores the intensity of burgeoning adolescence in a way I haven’t seen done before.

13. ALL THE BEAUTY AND THE BLOODSHED

Maybe my favorite new documentary since the one on David Wojnarowicz, and his presence here doesn’t even distract from Nan Goldin, whose work and life personifies that blur between the two.

14. ROTTING IN THE SUN

The movie that dares to ask, “What is the biggest dick onscreen?” in all senses of the word; pretty ingenious in its use of a meta-narrative (plus Catalina Saaverda, as great here as she was in director Sebastian Silva’s The Maid.)

15. THE NOVELIST’S FILM

My fifth Hong Sang-soo film and easily my favorite for what it withholds and also for what it provides in return.

16. TORI AND LOKITA

Reassuring (if depressing) that cine-activists like the Dardennes will never run out of subjects stoking their outrage at an unjust society; one of their starkest and most effective critiques.

17. FALLEN LEAVES

A strange but charming middle-aged romance between a supermarket worker (Alma Pöysti) and an alcoholic laborer (Jussi Vatanen) that could only come from veteran Finnish purveyor of deadpan humor Aki Kaurismaki.

18. THE UNKNOWN COUNTRY

While it takes a little time to gather momentum, Morrisa Maltz’s narrative-docu-roadtrip hybrid ends up a fresh approach to telling a story of not just one person (Lily Gladstone, great again) but of the worlds she inhabits and intersects with.

19. NO BEARS

Of all the meta-films Jafar Panahi’s made in the past decade-plus since his government began enforcing restrictions preventing him from making another more traditional (so to speak) narrative like Offside, this feels like a summation, a crescendo and hopefully not the final word.

20. THE ZONE OF INTEREST

No atrocities are shown in Jonathan Glazer’s holocaust film but their background presence seems to permeate every scene with the horror of being adjacent to genocide and living with it. What’s tangentially acknowledged and left up to the imagination becomes just as disturbing as if one were to face it head on.

ALSO RECOMMENDED:

- A Thousand and One

- All That Breathes

- Asteroid City

- Barbie

- BlackBerry

- Bottoms

- Full Time

- Godland

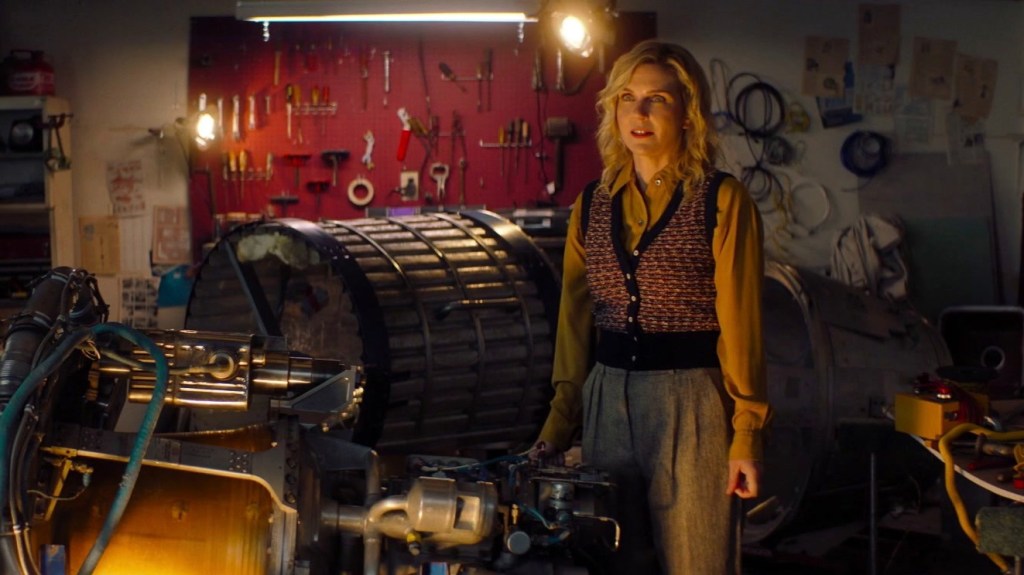

- Linoleum

- Of An Age

- Orlando, My Political Biography

- Pacifiction

- Passages

- Reality

- R.M.N.

- Scrapper

- The Blue Caftan

- The Boy and The Heron

- The Pigeon Tunnel

- The Quiet Girl

- You Hurt My Feelings