In the last entry, I stressed how content and form can both complement and enhance each other in a film. One of my more important takeaways from studying the art in grad school was the importance of good writing (content) and acting (form)—the absence of either one often an automatic blemish on the final product. Obviously, not only performances determine form, even if they’re the most crucial component of it. However, one should not value a film’s style any less in establishing its overall worth. In particular, a sense of place via its production and sound design can be just as crucial in making a great film as its screenplay or actors (as long as they don’t overshadow either one.)

Roughly a decade after grad school, entering my mid-late 30s, I had by then seen literally thousands of movies (probably closer to around 2,000, but that qualifies.) As with any medium, the more one absorbs, the better one can critically assess. I reached a point where I began responding more strongly to qualities I hadn’t seen before, as opposed to those which had become tropes or rendered stale through repetition. Woody Allen, for instance, grew less interesting to me (controversy/cancellation aside): his 21st Century work offered little variation on what had come before (give or take a Match Point), rendering him irrelevant and mechanical (I took to dubbing him the “Wood-bot”.) Why waste time on someone obviously past their prime with so much new (and unseen old) stuff attempting something different or at least advancing a fresh perspective?

Naturally, I praised unique, innovative performances: Daniel Day-Lewis’ ultra-specific persona and accent in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, Lesley Manville burrowing deep as an unglamorous but sympathetic lush in Mike Leigh’s Another Year; Nicolas Cage going for broke and director Werner Herzog expertly guiding him in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. I also valued screenplays that either told stories I hadn’t heard before (Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York pushing his trademark meta-ness to an extreme in exploring mortality vs. the permanence of art) or told in a way I hadn’t seen before (Leos Carax’s Holy Motors orchestrating an extended metaphor for what it entails to partake in a performance and inhabit many roles.)

Just as often, the look and/or sound of a film got my attention. I fell head over heels for Nicolas Winding Refn’s Driveand its deep dive into a Los Angeles milieu by way of its opening, splashy pink-font credits scored to Kavinsky and Lovefoxx’s seductive, retro-electropop “Nightcall”; I also found the throwback, low-budget, black-and-white New York of Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha incessantly charming. I instantly loved the near-magical conjuring of 1965 coastal Rhode Island Wes Anderson crafted for Moonrise Kingdom and the melancholy, concrete greys of Greenwich Village set just a few years before in Joel and Ethan Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis. Of course, each of these titles also had exceptional screenplays and performances (Frances Ha is unimaginable with anyone other than Greta Gerwig as the titular character) but their visual tableaux and soundtracks were beautifully in sync with them, creating multi-dimensional experiences one couldn’t replicate solely on the page.

Of the new filmmakers to emerge in the 2010s, Peter Strickland was one of the most driven by an uber-particular sense of style. Born in Britain in 1973, he broke through with his second feature, Berberian Sound Studio (2012). Toby Jones (then best known for starring in the Truman Capote film that was not Capote) plays a meek sound engineer working on a 1970s Italian horror film (the subgenre, giallo, is best exemplified by Dario Argento’s 1977 masterpiece Suspiria.) Strickland’s work is more of a psychological horror film, with Jones’ character’s sanity gradually ebbing as his personality fractures and real life becomes indistinguishable from the movie he’s working on. Rather than keeping tabs on an ever-more-convoluted plot, the film is most striking for its style, heavily drawing on giallo tropes (bold colors, intrusive music, graphic violence, an enveloping feeling of dread and the macabre) and also painstakingly recreating the look and feel of a period long since passed.

Berberian Sound Studio makes a formidable impression but its obtuseness doesn’t fully satisfy—by the end, while dazzled by its style and impressed by Jones (a gifted and consistently great character actor), I didn’t feel much of an emotional connection to what had transpired. Thankfully, Strickland avoids this trap with his next feature, The Duke of Burgundy (2014). Ostensibly set in what appears to be a small European village (it was shot on location in Hungary but its location is never explicitly identified onscreen), it has a style and sense of place as richly textured, realized and dominant as its predecessor; it’s also a big step forward in how he expertly utilizes these facets in service of his narrative, which is nearly as complex but far more resonant in how it invites the viewer to respond to its characters within this environment.

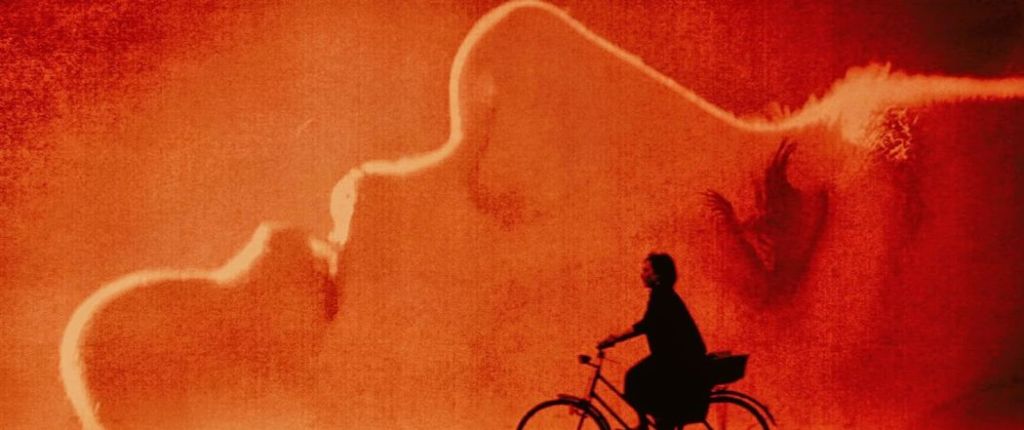

The film opens with Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna), a younger, pixie-like woman kneeling at a bucolic stream in what resembles an enchanted forest out of a fairy tale. She looks up longingly at the sky and then takes to her bicycle, riding through the woods as the opening credits commence. Scored, like the rest of the film to the baroque chamber pop of duo Cat’s Eyes (with breathy, Francoise Hardy-esque vocalist Rachel Zeffira), the credits resemble a picture book or perhaps a procession of twee, self-knowing The Smiths or Belle and Sebastian album covers, employing freeze frames, matte effects and various animation techniques (including fluttering butterflies—remember them.) It concludes once Evelyn reaches her destination: the posh home of Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen).

A single, middle-aged lepidopterist (one who studies butterflies and moths), Cynthia greets Evelyn with a curt, “You’re late” before letting her into the house. One immediately detects how curated the place is, as eloquently considered and conceived as anything out of Architectural Digest. Between the furnishings and the characters’ hairstyles and clothing, it also easily looks like it could be the 1970s, yet there’s something not-quite-restricted to that period suggesting this could be reasonably set during any time since that decade (it’s also devoid of devices such as cell phones or computers that would render the palette a deliberate anachronism.) Certainly, such an environment feels like a deliberate provocation, meant to invoke something retro without placing it in a concrete context. It fascinates not because it necessarily begs us to ask when is this actually taking place but more like why does it look like the past frozen in amber?

It’s a question that surfaces in nearly all of Strickland’s work, especially his next feature In Fabric (2018), which delves deep into home furnishings, fashions and department store interiors straight out of the 1970s and 1980s while not necessarily tied to either of those decades beyond their looks (really, the tale of a dress that murders people can be set anytime, anyplace!) In The Duke of Burgundy, however, it’s a tad more subtle. One could simply chalk it up to the director’s preference for era-specific stylistic choices—a love for visual motifs from the years constituting his own childhood. It surely distinguishes itself from an alternate universe version of the film explicitly set in the present where Cynthia and Evelyn post on social media and include slick PowerPoint presentations in the former’s lepidoptery lectures.

While unignorable, however, Strickland’s stylistic choices primarily help to set an overall tone—an off-kilter one, for sure, as The Duke of Burgundy occasionally shifts into experimental, dreamlike sequences that do not so much move the narrative forward as offer peeks into Evelyn’s and especially Cynthia’s subconsciouses. In direct contrast to heightening this overall sense that something’s just a tad awry, these visuals also end up exuding a sense of coziness, maybe even some warmth. Cynthia has obviously put a lot of thought and care into designing her home and every consideration from its mood lighting to the textures of its furniture and knickknacks feels welcoming: a real, lived-in home rather than a sterile museum. The idyllic, heavily forested and sun-kissed (even when perpetually rainy, somehow) village settings are similarly pastoral and inviting.

This blend of peculiarity and familiarity is also palpable after Evelyn enters Cynthia’s home and the later commands of her, “You can start by cleaning the study.” It initially appears that Evelyn is Cynthia’s cleaning lady, and not a sterling one at that. Cynthia comes off as a stuffy taskmaster, sitting in her chair and reading while ignoring Evelyn as she scrubs the floor beneath on her hands and knees. Cynthia remains unsatisfied, ordering Evelyn to rub her feet and then wash her underwear by hand in the bathroom sink. Still disappointed by Evelyn’s work, Cynthia announces that it’s time for “A little punishment.” She takes her by the hand, dragging her into the bedroom where, behind a closed door, we hear what sounds like Evelyn being repeatedly spanked, or perhaps whipped.

However, the next shot reveals what’s really going on: as the two women lie in bed together, lovingly caressing each other, we see that Evelyn is more than just Cynthia’s maid (or perhaps not one at all.) The whole thing is a charade, an act, a BDSM relationship between the two women with defined dom and sub roles. Suddenly, Cynthia’s brusque demeanor makes perfect sense, as does much of her odd behavior—for instance, exactly why she drinks copious amounts of water before one of Evelyn’s subsequent visits is never shown but discreetly implied that it has something to do with urination as a sexual act. That it’s all a performance is a clever twist; had this been a short rather than a feature, it would’ve been a neat place to end on.

Fortunately, Strickland takes this further by gradually revealing another turn: while Cynthia plays the part of the dom, it’s clearly Evelyn calling the shots in their relationship, making suggestions and writing down what Cynthia should be doing and saying when playacting with her. Increasingly, Cynthia can’t help but relay her discomfort with her role, which as an actress Knudsen expresses beautifully to the point where it’s heartbreaking to view her growing distress. At one point, a platinum blonde and potential femme-fatale only known as The Carpenter (Strickland regular Fatma Mohamed) visits them to provide measurements for a coffin-like container which Evelyn could sleep in under Cynthia’s bed. Once determined this object could not possibly be completed in time for Evelyn’s birthday (it’s a gift!), the carpenter suggests an alternative present called a ”human toilet”: note the childlike glee on Evelyn’s face at this mention and, in contrast, the utter bewilderment on Cynthia’s, who abruptly leaves the room, citing another appointment as an excuse for her brash departure.

Real, unignorable emotions increasingly invade the performative aspects of Cynthia and Evelyn’s relationship. Cynthia finds herself unable to recite her lines with conviction while Evelyn, tempted by The Carpenter, becomes impatient, telling her love, “It would be nice if you did it without having to be asked.” If it sounds like pure soap opera, rest assured stylistically it is far removed from that genre. As the relationship becomes strained, the score is less melodic with electronic droning noises threatening to completely smother the strings, harpsichord and cor anglais from before. Similarly, the lighting gets darker and opaquer while the camera moves ever-more-deliberately with copious slow-as-molasses vertical pans nearly rendering both interiors and bodies as abstractions.

The film’s title refers not to European royalty but the English term for a species of butterfly, Hamearis Lucina. Why Strickland chose this particular species is best left to lepidopterists, but his use of butterflies as a motif is more relevant. When considering this insect, one can’t help but think of the notion of transformation—how a caterpillar passes through multiple stages to become something radically different (from a ground dweller to a flier with colorful wings.) In that sense, both Cynthia and Evelyn struggle (to varying degrees) in transforming themselves and each other. A stark reminder of this is omnipresent in Cynthia’s home: cases and cabinets teeming with pinned butterflies, all of them transformations that eventually hit a dead end, preserved as memories but not ongoing entities like our heroines. The two women reach a cathartic moment, Evelyn consoling Cynthia about their playacting, “If this is what it does to you, I can change.” Rather than evolving like a successful transformation, however, this relationship more resembles a Mobius strip—following this confrontation, the film ends as it begins with Cynthia once again drinking her water and reviewing her notecards as Evelyn shows up at her front door.

Still, the butterfly motif is not just there for the benefit of the film’s central relationship. In the lecture scenes, one learns that Evelyn herself is a budding lepidopterist, her desire to dominate made flesh as she asks a lecturer pointed questions seemingly to bring attention to herself while a vaguely embarrassed Cynthia looks on. As the camera slowly pans across the lecture’s audience, not one man is present, only women. Further heightening the film’s off-kilter sensibility, some of the women are so extensively made-up they resemble men in drag (much like a Roxy Music album cover); the gleeful presence of the occasional mannequin in the background of said audience pushes this off-ness even further. Gradually, one realizes there are no actual men in the entire film! The Duke of Burgundy is itself a transformative realm, a society of women playing all parts. The butterflies themselves are remnants of a completed evolution; its central love story conveys that whatever our aspirations may be, humans as individuals are subject to a continual evolution without end; as couples, an end only arrives when one participant or in some cases, both are no longer willing to evolve.

We leave Cynthia and Evelyn at an impasse—their relationship is intact, for now, but who is to say what potential it has when it appears to be stuck in a cocoon? Similarly, one can appreciate new films for their familiarity, but when do they start seeming stale? Like The Duke of Burgundy, the remaining titles in this project will emphasize new ways of seeing and storytelling as recent examples of the medium’s continued evolution.

Essay #21 of 24 Frames

Go back to #20: Stories We Tell.

Go ahead to #22: Cemetery of Splendour